When choosing a horse, hind leg conformation is an important consideration because a horse with good hind-leg conformation is more likely to stay sound through the years.

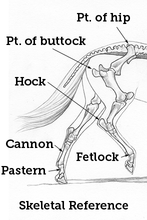

Skeletal apparatus of rear leg

Conformation of the hind legs and hindquarters of a horse is important because it plays a major role in how a horse moves and in his soundness.

Conformation of the hind legs and hindquarters on a horse plays a major role in how the horse travels, whether he will have limb interference, whether he will be fast or slow, clumsy or agile, suffer from locked stifles or develop hock problems such as spavin or curb.

The hindquarters provide most of the propelling power of the horse, with their direct hook-up to the backbone. The groups of muscles in the hind legs are larger and more powerful than those of the front legs.

The hind legs must be able to hold the entire body weight at times, and are also important when the horse "puts on the brakes" for stopping.

Any horse that must stop and turn quickly needs strong, well-made hindquarters, as does a horse that travels up and down steep hills or over jumps.

The horse's hind legs are less subject to lameness than the front legs, because the hindquarters suffer less concussion and trauma, carrying less weight.

Judging conformation from a rear view

Viewed from the rear when the horse is standing squarely, each hind leg should be straight--from buttock to hoof. All the joints should be in a straight line.

Hocks and fetlock joints are easiest to see, but the hind leg starts at the pelvis and croup (where the leg attaches to the backbone); the angle and set of the hocks and lower legs is determined by structure of the pelvis, hips and stifle joints above them.

A line dropped from the point of the buttock (or drawn with a straight-edge on a photo) should bisect the leg--going down the center of the hock, cannon, fetlock joint and pastern. A straight leg gives equal distribution of weight on various parts of the leg, and equal strain and pressure on all parts--with no one area suffering extra wear or trauma.

A perfectly straight hind leg, viewed from behind, is considered ideal but many good horses have slightly turned in hocks (and hence slightly turned out feet).

All wild members of the horse family are a little closer at the hocks than at the feet, but for best hind leg construction in an athletic horse, the cannon bones should be vertical and parallel. It is quite acceptable, however, to have the hocks turned slightly in and the hind feet toeing slightly outward, as long as the cannons are vertical.

Did you know?

In nature, most hoofed animals--deer, elk, buffalo, moose, wild asses, zebras--are "cow hocked", which is a much stronger construction than bowlegged hocks.

Base wide conformation is when the hind feet are too far apart (farther apart than the legs at the thighs). The most common type of base wide conformation in hind legs is cow hocks. The hocks are too close together and the feet too wide apart. The hocks may point toward one another and the cannon bones are closer together at the top than at the fetlock joints.

The feet may be fairly straight, or might be widely separated and pointing outward. Extreme cow hocked conformation puts strain on the side of the hock joints and can cause bone spavin (enlargement due to inflammation and new bone growth).

Viewed from the side, the cow hocked horse may also be sickle hocked (see below). Spavin is common in horses that do not travel straight behind, due to a twisting action of the hock joint. This deviation from straight action also affects the lower leg, putting more strain and twist on cannon and pastern, putting the fetlock joint more at risk for stress injury. The inside portion of the foot must carry more weight, which can lead to uneven wear, cracks and bruising.

The cow hocked, splay-footed horse may throw his legs outward, but many horses with this type of leg structure tend to swing them inward and interfere when traveling, striking each foot against the opposite leg, generally hitting the fetlock joint. This is because when the toed-out foot is picked up, the fetlock joint folds crookedly instead of straight, bending the foot to the inside.

The inward swing of the foot is accentuated when the horse is wearing shoes, due to added weight on the foot. The fetlock joints may be seriously injured by being constantly hit with the opposite shoe.

Interference (front or rear) may be sporadic and you can't always determine from the build of the horse whether or not he will hit himself, nor at which gaits he is most likely to do so. You need to watch him travel. Horses that strike the opposite leg at a slow trot may not do it at a fast trot, or vice versa. Some horses don't hit themselves at a walk, but interfere badly at a trot. Some throw their feet inward when traveling up or down hill. The angle of foot flight may be changed by speed or the way the horse travels uphill or down, or through uneven terrain or obstacles.

In some horses the hocks are too close together but cannon bones and feet are vertical from there down, rather than splayed out. This type of construction is not as bad, and the horse may not have interference problems. Some horses that stand close behind, however, will interfere, especially at the end of a long ride or race when they are tired.

Note this:

A horse that does not interfere when running free might interfere when shod and carrying a rider. To effectively evaluate a horseâs action, you need to see him move--and not just while walking and trotting in a level barnyard.

The opposite of base wide is base narrow. When viewed from behind, the base narrow horse has hind feet too close together. Distance between the center of the feet is less than the distance between the center of the legs at hocks and thighs. Bowlegged horses (with hocks too wide apart) are often base narrow at the fetlock joints or feet.

A base narrow, bowlegged structure is most common in heavily muscled horses; the hindquarters are wide and bulky (stifles too far apart). The leg bones are far apart at the top and at the hocks, but come closer together toward the ground. There is excessive strain on the outside portions of the leg (more stress on bones, ligaments and joints).

The hocks are often wide apart (and may point slightly out rather than slightly inward as they should) and the cannon bones slant inward to the feet. The toes generally point straight forward or may even point inward. Weight is carried on the outside edges of the hoofs.

Bowlegged hock construction puts great strain on the hock and fetlock joints. The hocks may develop bone spavin, bog spavin or thoroughpin (soft swellings on the upper sides of the hock). The horse with this type of hock structure tends to swivel the hocks outward at each stride, putting a twist on the hoof each time it takes weight.

Keep in mind:

Leg deviations (front or rear) don't always come in pairs. One leg may be more pigeon-toed or splay-footed than the other, or have a more crooked cannon bone. A horse with one leg more crooked than its mate may interfere only on one side.

When watching the horse walk or trot (from behind), you can see the foot placed on the ground and twisted as the hock pushes outward to take the weight of the body--and is finally straightened again as it pushes off.

The twisting motion of the hocks prevents the foot from coming to the ground squarely and the turning action puts more stress on the outside of the hoof wall. This can lead to cracks and bruises, or even ringbone due to stress on the pastern or coffin joints.

The feet may be facing forward or pigeon toed. Bowlegged horses are often toed in. In some horses, the legs may be fairly straight down to the hocks, but become base narrow from there down. Bowlegged and base narrow structure is weak conformation, and the horse may experience limb interference at fast gaits.

The hocks roll outward and feet come too close together. The hind leg does not have much forward reach and has a lot of wasted motion caused by the twisting of the hock as the foot is lifted from the ground. This reduces efficiency for speed. The horse wonât be a good athlete because he cannot make efficient use of his muscle power for traveling forward or stopping quickly.

Bowlegged and cow-hocked horses (two extremes of poor hind leg conformation) are both handicapped for producing maximum speed; these deviations create a loss of energy and efficiency. The feet turn inward or outward instead of moving straight forward. The crooked leg also hinders agility and coordination for precise athletic maneuvers.

Judging conformation from a side view

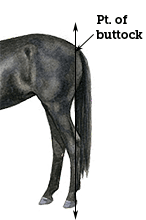

When viewed from the side, the cannon bone should be vertical and directly under the buttocks. The back of the hock and the back of the cannon should be perfectly straight--perpendicular to the ground when the horse stands squarely.

The ideal degree of angulation in the hock

A line dropped from the point of the buttock should touch the point of the hock, go down the back of the cannon, the back of the fetlock joint, and hit the ground behind the heel of the foot.

If a line is dropped from the point of the buttock, it should touch the point of the hock and follow the back of the cannon on down to the back of the fetlock joint, hitting the ground a short distance behind the heel of the foot. This is the ideal degree of angulation in the hock joint.

If the hock joint is too straight (set too far underneath the buttocks toward the body of the horse) or too angled (hock and cannon not perpendicular to the ground, with hind feet too far under the horseâs body and the cannon bone angled) there can be serious problems.

An occasional exception is seen in horses with very long quarters and a more protruding buttock than average. The hock angulation may be perfectly normal, but the line dropped from the buttock could miss the leg slightly because of the long buttock.

The opposite sometimes occurs, if a horse has a too-short rump; a line dropped from the buttock goes in front of the back line of hock and cannon, even though the hock angulation is correct. A very sloped rump could also give this result.

Sickle hocks

If a horse has too much bend at the hock joints (cannon bone sloped rather than vertical), this adds more stress and strain to the joint, and creates a type of conformation called sickle hocks. This hind leg structure makes a horse more likely to develop curb (enlargement of the tendon at the back of the hock due to excessive strain), bone spavin at the lower hock joints (enlargement on one or more of the hock bones), or bog spavin (permanent swelling in the soft tissues of the hock).

A horse that is extremely sickle hocked may also damage the bottom or back of his hind fetlock joints when running hard if they go clear to the ground.

If you don't have an opportunity to watch him travel, look closely at the insides of his legs to see if there are any nicks, scars, lumps or hair missing, in areas where he might be most likely to hit himself. Some horses interfere only when shod, or when shod sloppily, or when tired.

If a horse is sickle hocked, a line extended up the cannon bone is at such an angle that it completely misses the buttocks. The horse's feet are too far underneath his body. They are not directly under his hocks and buttocks as they should be.

Sickle hocked conformation is detrimental to speed as well as making the horse more susceptible to leg problems and lameness. In order to have strong thrusting power and speed, the hind leg must act as a perfect pendulum; the hocks must be able to straighten quickly as the hindquarters propel the horse forward.

The sickle hock is hindered in maximum straightening and backward extension of the leg, making a weaker push-off. Straighter hocks and stifles are better than excessively bent ones for producing speed.

When there is too much bend in the stifle and hock joint, there is considerable loss of time and energy spent in straightening the joints at each stride. There is more circular motion before the hock can get into position to drive the body forward.

A straighter leg can swing farther and faster, beginning its forward motion from the point of the toe and driving the body forward from a straight line (no loss of motion between the ground and the top of the hock). The straighter hock and stifle can be moved in pendulum fashion far more rapidly, with a greater length of stride. By straight, we mean a leg with proper hock and stifle angulation, not a leg with a too-straight hock and stifle joint.

Post legged

Hocks that are too straight (not enough bend) put the whole hind leg too forward--not directly under the buttocks. A horse is considered post-legged (hocks too straight) if the joint angle between the upper leg bone and the cannon bone is more than 170 degrees. Viewed from the side, if a hind leg is too straight, a line dropped from the buttock falls in back of the cannon; the hock is set forward almost under the stifle; the leg as a whole is almost as straight as a fence post. The tibia (above the hock) is almost vertical, rather than having a normal 60 degree slope.

Post-legged structure can cause locked stifles. Since the stifle joint is also too straight, the patella (kneecap) sometimes slips out of position and locks the leg in backward extension. The straightness of the stifle limits the movement of the ligaments across the patella, which not only tends to lock this small bone in the wrong place at the wrong time, but can also lead to degenerative arthritis in the stifle joint.

If the hind leg is so straight that the stifle is upright (with the femur--the bone above the stifle joint--and the patella nearly in a straight line) there is great risk for dislocation of the patella and locking of the stifle joint.

Horse resting back leg

The normal horse rests a hind leg by hooking the patella over the bulge at the end of the femur thereby locking the stifle and enabling him to rest a leg without muscular effort to keep it steady.

The normal horse rests a hind leg by hooking the patella over the bulge at the end of the femur (the big leg bone above the stifle joint). This locks the stifle and enables him to rest a leg without any muscular effort to keep it steady. He can lock and unlock the stifle as he wishes, to stand with a hind leg cocked.

But in a horse with too-straight stifles, the patella may inadvertently catch and hook any time the joint is extended--when he is walking, trotting or galloping. In a horse with proper hind leg conformation, the stifle angle is about 135 degrees.

When the joint is extended (to about 145 degrees) the patella hooks on the femur. If the post-legged horse has a stifle angle of about 140 degrees to begin with, it doesnât take much of a misstep to move it a few more degrees and hook the patella--which is a serious problem if it happens while he is traveling.

The post-legged horse with too-straight hocks may also develop bone spavin and arthritis, as well as bog spavin (swelling in the soft tissues of the hock) because of extra strain on the front of the hock joint capsule. There is constant tension on the small joints within the hock, which irritates the joint capsule and joint cartilage.

The chronic swelling of bog spavin is caused by too much lubricating fluid in the capsule--a result of pulling and irritating the capsule, causing the lining to produce excess fluid. The restriction of the tendon sheath when the hind leg is moving (due to improper hock angle) can also lead to development of thoroughpin. The too-straight leg is easily injured by hard use because of this extra strain on the flexor tendon and its sheath and on the upper part of the suspensory ligament.

A post-legged horse may suffer excessive concussion on the hind feet because of the way the straight leg causes the feet to stab directly into the ground at each stride, with little flexing action. This can lead to cracked hoofs, sole bruising and other concussion related problems within the foot.

Fourth in the series

This is the fourth in a series of five articles that are written by the author of "The Horse Conformation Handbook

." This book, illustrated by Jo Rissanan (a frequent EquiMed contributor), is a must read for anyone interested in a detailed understanding of horse conformation.

Previous The Importance of Correct Front Leg Conformation

Next in the series Horse Conformation - Horse Conformation as a Whole - Can He Do the Job?.