The head-neck-shoulder hookups in a horse help determine his ability to flex and collect himself, and play a role in his agility and athleticism. The horse uses his head and neck for balance in a pendulum effect to counteract actions of the hind end of his body. He can raise or lower his head to help maintain or regain his balance, and to help adjust his speed or direction.

Horse face length vs. Neck length

The face length of the horse should never be longer than the neck length. Also, look for a clean and refined throatlatch.

The head should never be longer (measured from poll to upper lip) than the length of his neck (measured from poll to withers). The throatlatch area where the neck meets the head behind the jaws should be well defined and not too thick and meaty. A nice clean throatlatch gives the windpipe more room and aids breathing ability when the horse is working hard. It also allows for greater range of motion for head and neck. If the throatlatch area is too thick with excess fat/muscling, the windpipe, esophagus, blood supply, etc. are restricted when the horse tucks his head. The jaws and throatlatch hookup should be wide; a narrow throatlatch constricts the airway.

A short thick neck is acceptable for a draft horse that needs pulling power, but is encumbering for a riding horse. The neck is the crucial link between head and shoulders and there must be sufficient length for the horse to swing his head up and down for effective balance. Measured from poll to withers, it should be proportionate with the rest of the body--about 1/3 of the horse's overall length. It should be fairly long and slender, slightly arched along its topline and relatively straight on its underside.

If the neck is relatively long, it must have a small rather than a large head, or the horse will be overbalanced and too heavy in front. The head and neck (in relation to the body) are like a small weight at the end of a lever that can be used to balance a larger weight (hindquarters) at the other end.

A galloping horse uses this balancing principle. When the hind feet are hitting the ground and pushing the horse forward, head and neck are raised. Then as the front legs hit the ground the neck and head are lowered, to help raise and counterbalance the hindquarters that are lifting--so the hind legs can come forward again for another stride. As hind legs hit the ground, the horse shifts his weight back again so he can get his front legs off the ground to come forward, and the cycle repeats itself--head and neck rising, reaching forward and down, then rising again. A long neck is usually more desirable than a short one; the horse can raise and lower his head more easily, to whatever position is needed for balance.

Transition from neck to shoulder

The neck transitions to the chest at or above the point of the shoulder for best balance.

The way the neck is set on the shoulders is also important for proper balance. Viewed from the side, there should be a smooth transition from shoulder to neck, with the neck set neither too high nor too low. If the neck is so low-set that the horse has hardly any breast below the base of his neck (the neck set on horizontally), he will always seem to be leaning too far forward, traveling heavy in front; he will be hard to collect. He has poor balance and impaired agility. The base of the neck (departure from the chest) should be level with the point of the shoulder or higher. If the head and neck are carried too low, shoulder action is restricted; the forelegs canât be raised high enough nor forward enough for a good stride, which reduces the horseâs speed and jumping ability.

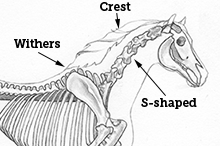

The 7 neck bones make an S-shape, with the top curve right behind the head and the bottom curve joining the thoracic vertebrae in the area between the horseâs shoulders. The base of the neck hooks onto the first long-spine vertebrae that form the withers. The size and shape of these two curves (behind the head, and hooking into the shoulders) determine the length, shape and functional mobility of the neck.

Mobility of the head depends on the first two vertebrae. The first neck vertebra--which hooks onto the skull and starts forming the neck, is the atlas. It lies right behind the poll and forms a curved ridge. The atlas can slip over the second vertebra in such a way that the horse can nod his head up and down without moving the rest of his body; this enables him to flex at the poll and make a tight bend in his neck, bringing his chin down toward his chest. This neck flexibility makes it easier for him to flex at the poll.

Neck length proportional to leg length

For best balance and eye appeal, the length of a horse's neck should be about the same length as the horse's front legs.

Neck length should be proportionate to the body and about the same as the length of the front legs. Another guide is that the neck (measured from poll to top of withers) should be about 1.5 times the length of the head. A neck that is exceptionally short and thick is usually a hindrance to balance and precise action, since it has less ability to move freely and quickly. The horse has less use of head and neck during athletic movements, and is more prone to clumsiness. A short, thick neck and a thick throatlatch limit flexion at the poll and inhibit side-to-side mobility. Being able to flex and bend is crucial for proper balance and collection.

A short neck is often a thick neck, with greater muscle development, making it heavy and less supple. A short, heavy neck that cannot flex adequately to bring the head back closer to the body also adds more weight to the front end of the horse, which reduces his agility. A short neck generally goes hand in hand with a short, upright shoulder. And since the neck muscles help pull the shoulder and front leg forward, a short neck means a shorter stride. The horse with a short neck may have a quick burst of speed, but because his stride is shorter, he must move his legs much faster than a longer striding horse, with more repetition of movement to make up the difference--adding stress on his legs and body.

A short, heavy neck and fairly large head can be an advantage to the draft horse, however, as he leans into his harness to pull a heavy load, with plenty of neck muscle to help move the shoulders. The heavy head, neck and shoulders help him in pulling.

A too-long neck for a riding horse may put the horse's center of balance too far forward for agility and balance. A very long neck is usually less flexible than one of average length. Since the horse has only 7 vertebrae in his neck, regardless of whether the neck is long or short, a long neck has more distance between each of the joints (longer-bodied vertebrae) and is thus less flexible. The shorter neck has its joints closer together and is more flexible for its length.

A horse with a too-long neck may have trouble responding properly to the bridle (not collecting adequately). A long, slender neck is also accompanied by a narrow throatlatch and impairment of the airways. The muscles of a too-long neck may be underdeveloped, and the horse may tire too quickly when working hard. When he tires, he may drop his head, putting too much weight on his forehand, and his stride will become weaker and uneven because it is no longer being helped by the neck muscles.

The muscles of the neck help pull the shoulders and front legs forward at each stride. Neck muscles can contract (and extend) about two thirds of their actual length. Thus a short-necked horse with a short upright shoulder will have a short stride. If the neck muscles are poorly developed or too short, the horse will not be able to run as fast or as far as a horse with strong neck muscles of proper length.

Importance of neck shape

Even if the neck is the proper length for good balance, it may have structural features that make it more difficult for the horse to have perfect mobility and balance, especially when carrying a rider. Some types of neck construction make it harder to collect the horse--creating more challenge when trying to create communication through the bit.

Neck structure from crest to withers

The shape of the internal neck structure relates to the functionality of the neck.

The shape of the neck (formed by the shape of its bone structure) is actually more important than its length. Every vertebra in the neck has a different size/shape, and the joints between them cause the bones to fit together in an S-shape. The column of vertebrae that make up the neck bones does not follow the curve or line of the neck (which is made up primarily of a large mass of muscles), but instead forms two curves.

There is a small curve at the top, just behind the head (creating the crest), and a larger curve at the bottom where the neck hooks into the taller vertebrae of the withers (between the shoulders). The shape of the neck--whether the horse has a ewe neck, swan neck, bull neck or a normally curved neck--depends on the proportions of the S curve of the vertebrae.

Head, neck and shoulders in action

Highly athletic and trained horses exhibit both beauty and functionaility, in part due to their head, neck and shoulder conformation.

The most important aspect of the neck is the shape of the lower curve in the S. If that lower curve is short and shallow (making the base of the neck attach high on the chest rather than low toward the breast) the horse will have the best neck hook-up for easy maneuverability and collection; it will be easier for the rider to get him to carry his head and neck properly for good flexion. Straightening out that lower curve (as the horse must do to collect himself) is much easier for the horse with a curve that is already short and shallow.

If the lower curve is too large and deep, attaching low on the chest, the horse will be ewe necked, even if the head is set on the neck at a good angle. If the neck is too low at its base, the head is carried too high; itâs hard to get the horse to lower his head or flex his neck. The thickest part of a horse's neck is along the lower curve of the S. Thus a horse with a long, deep lower curve (ewe neck) has the widest part of his neck lower than the midpoint of the shoulder. By contrast, the widest part of the neck on a horse with a properly arched neck (with a flat, shallow lower curve, coming higher out of the shoulder area) is higher, with better potential for good muscle development and maneuverability.

The upper curve of the S determines how the head sets onto the neck. A short upper curve creates an abrupt attachment and acute angle at the throatlatch (hammerhead) and the head is often carried too high, unable to flex at the poll. A medium-to-long upper curve makes a better angle at the throatlatch, enabling the horse to flex better at the poll.

The neck of a well-proportioned horse is well arched, with a flat, level area just behind the ears where the skull attaches to the first vertebra. The length of neck can often be determined by the way the horse carries his head, and the way the neck joins the withers. If these hook-ups are graceful and proper, the neck is the right length. If they are abrupt, the neck is probably too short. If they are loose-looking, with the head improperly attached to the atlas vertebra, the neck may be too long. If the neck fits properly onto well sloped shoulders, it will be in balance with the rest of the horse.

Ewe neck

The ewe-necked horse has an upside-down neck; the top line is concave rather than arched, and the head usually forms a right angle to the neck at the throat instead of a curved arch. There is a downward dip in the neck, ahead of the withers, and the muscles at the bottom surface of the neck are thicker. This type of neck structure makes it almost impossible for the horse to flex at the poll.

If the lower curve of the S is too deep and wide (no matter what the size and shape of the upper curve), the horse will have a ewe neck--with a hollow ahead of the withers. Many horses with this neck structure also have an upright shoulder; the upright shoulder and the long lower curve of the neck tend to go together.

The ewe-necked horse has trouble getting proper bend in his neck for flexing at the poll and giving to the bit. It is harder for him to flatten out the lower curve for proper flexion. Thus it is harder for a rider to collect him and get him to balance his weight farther back, to take more weight on his hindquarters and less on his front legs. This type of horse travels heavy in front, especially when carrying a rider, making him less agile and more prone to stumbling. If the horse raises his head much above his withers, it becomes even harder for him to give to the bit, due to the upside-down curve of his neck.

The ewe-necked horse with a short neck tends to have a thick neck and the ewe-necked condition may not be as obvious as in a horse with a longer neck. The short-necked horse has a short upper curve (behind the head), making a coarse, thick juncture between head and neck (hammerhead) with very little flexibility. Many of these horses are difficult for the average rider to train and collect--due to the inflexibility of the head-neck juncture--and they easily become hard-mouthed.

The ewe-necked horse with a long neck has a longer upper curve behind the head (creating a small crest at the top of the neck) but the basic neck structure is still concave rather than arched. The dip in front of the withers makes a kink in the neck when the rider asks him to flex. It is easier to try to collect this type of horse when the head is relatively low rather than too high. When the head is high, the kink in the neck is accentuated, tightening all the neck, shoulder, back, loin and hindquarter muscles (creating stiffness and a poor way of traveling).

Swan neck

This neck does not have proper topline, but it is not as obvious as the ewe neck. With a swan neck, the top one-third arches nicely (and the head/neck hookup is fairly normal, with a good throatlatch), but the bottom one-third (nearest the withers and shoulders) is concave, like a ewe neck. This type of neck is often set too low on the chest, with the base below the point of the shoulder. Withers may be prominent, with a dip in the neck ahead of the withers, putting the same kink in the neck as a ewe-necked horse.

Like the ewe neck, the swan neck inhibits proper flexion because of poor angle and hookup, and the horse tends to carry his head too high, interfering with proper bit contact. Bit pressure tends to make him throw his nose in the air and become rubbernecked, evading proper contact and control. If a horse has a long swan neck, he may lean on the bit and tuck his nose to his chest (and get behind the bit) rather than elevating his back and collecting properly. This type of neck is easily over-bent, with the chin touching the breast and the horse avoiding proper bit contact and control.

The way the neck is set on the shoulders is just as important as the way the head is set onto the neck. The neck and shoulder hook-up affects the shape of the neck. The neck should emerge from the shoulders fairly high, with a well-defined breast area below it. If the neck is set too low (like that of a zebra, with the neck starting so low it appears to be coming from between the front legs), with no visible breast below it, the neck is almost as deep (thick from top to bottom) as the body and the horse has little flexibility.

Straight neck

Some horses have no arch at all in the neck. There is no concavity or convexity to the top or bottom line of the neck; the top and/or bottom lines are perfectly straight. Some horses have a nice upward curve on the bottom of the neck, but a straight topline with no crest at all. Some necks are so straight, top and bottom, that there is no visible throatlatch; the neck looks like a long slim version of a zebra neck. A horse with a straight neck is limited in ability to flex and balance properly.

Second in the series

This is the second in a series of five articles that are written by the author of "The Horse Conformation Handbook ." This book, illustrated by Jo Rissanan (a frequent EquiMed contributor), is a must read for anyone interested in a detailed understanding of horse conformation.

Previous The Importance of Conformation When Selecting a Horse

Next in the series Horse Conformation - Importance of Correct Front Leg Conformation.