Conformation of feet and legs play a role in determining speed, athletic ability, and whether or not the horse will stay sound. The front legs carry more weight than hinds and are subject to more concussion and stress. Conformation faults in front legs can have more serious consequences than faults in the hind legs.

Conformation as key to speed, athletic ability and soundness

The front legs carry more weight than hinds and are subject to more concussion and stress. Conformation faults in front legs can have more serious consequences than faults in the hind legs.

Foreleg conformation (from shoulder to hoof) determines length of stride. The primary function of the front legs is to support most of the horse's weight, absorb the shock of concussion, and lift the body for the flight phase of each stride. Strongest construction consists of relatively straight legs with sturdy bone structure, big flat knees, and well-shaped fetlock joints.

Straightness

Ideally the forelegs should be straight--forearms directly above the cannon bones, and the cannon bones at right angles to the ground when viewed from front or side. Both legs should bear weight equally. Toes should point to the front, and hoofs should be the same distance apart as the distance between the forelegs where they join the chest.

A line dropped from the point of the shoulder should go down the center of the front leg, bisecting forearm, knee, cannon, fetlock joint, pastern and hoof. A line dropped from the front of the withers should go down the center of the front leg (side view) and barely touch the heel of the foot or be right behind it. If a line going up from the fetlock joint hits the middle of the withers, the forelegs are set too far back under the horse; he probably has an upright shoulder.

Most horses are not perfectly straight. Some faults can be tolerated if they are slight (not hindering speed or soundness) and symmetrical on both legs. Keep in mind that very few horses have all the bones and joints facing perfectly straight forward, and that no two front legs are exactly alike. Even on the same horse there will be slight variations; the left leg rarely matches the right one perfectly.

Determining straightness of foreleg

A line dropped from the point of the shoulder should go down the center of the front leg, bisecting forearm, knee, cannon, fetlock joint, pastern and hoof.

The leg bones in one or both forelegs may be slightly offset at the knee or fetlock joint, or slightly rotated, or may leave the joint at a slightly sideways angle instead of perfectly straight. The important thing is to be able to assess the straightness (or crookedness) and determine how the leg structure will affect the horse's movement (speed and agility) and future soundness.

Base wide

If front legs are farther apart at the feet than shoulders and forearms, this crookedness may start anywhere from elbows to fetlock joint. A turned-in elbow makes the leg turn outward. Base wide structure is also found in horses with narrow chests. Most base-wide horses are splay-footed, which causes the feet to break over to the inside and wing inward, often leading to interference (striking the opposite leg).

Most foals toe out slightly because they are narrow in the chest. Usually they become straighter as they grow and fill out, as the chest becomes wider. Splay-footed youngsters are more apt to straighten as they grow than are pigeon toed foals (toes turned inward), since filling out the muscles of the chest won't change the toe-in stance.

In a base-wide horse, the inside portion of the limb is under greater stress, especially if he is both base wide and splay footed. Ligaments at the inside of the fetlock joints and pasterns are always under strain. Windpuffs (swellings in the fetlock joint) generally occur if the horse is worked hard. The joint capsules and tendon sheaths may be disrupted and stay filled with extra fluid. Ringbone and sidebone may occur on the inside of the feet.

The inside aspect of knee joint and cannon bone suffer more stress and concussion, making the horse likely to develop splints on the inside of the leg. The hoof is worn excessively on the inside because it gets more wear. Splay-footed horses generally wing their feet to the inside whether they are base wide or base narrow, picking up the foot to the inside. A few horses are base wide and pigeon toed, which puts even more stress on the lower leg.

Base narrow

A horse with feet too close together often has large pectoral muscles and a wide breast. Base narrow structure is generally accompanied by pigeon toes. This puts strain on joints, often leading to windpuffs and to ringbone or sidebone on the outside portions of the feet. The hoof wall is worn excessively on the outside edge since the feet break over to the outside and land harder on the outside portion.

Base narrow, pigeon toed horses generally paddle, swinging the feet outward. This creates wasted motion as the lower leg and foot is flung to the outside at every stride, cutting down on speed and agility. A pigeon toed horse will paddle whether he is base narrow or base wide.

A few horses are base narrow and splay footed, putting even greater strain on the limbs below the fetlock joint. They often go lame if used hard. The base narrow, splay-footed horse will generally strike himself because the feet wing inward and are very closely placed to begin with. He may also âplaitâ, putting one foot directly ahead of the other. This creates poor balance and less stability--and if the advancing front foot strikes the other leg, the horse may stumble.

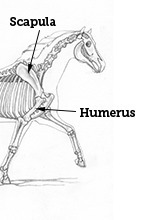

Upper arm

The arm bone (humerus) goes from elbow to shoulder. The length and angle of this bone has an influence on the action and stride of the front leg, determining how tightly the elbow and leg joints can flex (bend) and how far forward the entire leg can extend when the horse is moving. If the humerus is long, it gives more strength and power (more leverage action) to the attached muscles. The additional length increases the range of motion in the front leg, creating a greater arc at the lower end of the bone, at the elbow.

Showing humerus in relationship to scapula/shoulder and elbow

A long humerus gives more strength and power and increases the range of motion in the front leg.

A long humerus is desirable for speed, but it should not be disproportionately long compared with the shoulder blade or this makes for relatively short shoulder muscles--which would restrict the movement of the upper arm.

The humerus is of desirable length if it is 50 to 60% the length of the shoulder blade. This puts the elbow beneath the front of the withers. The humerus is too long if it is more than 60% the length of the shoulder blade, limiting freedom of action.

By contrast, if the humerus is too short, the horse will have a short, choppy stride. A short arm bone is usually quite horizontal, making its angle with the shoulder less than 90 degrees. This increases concussion to the leg, due to the choppy stride. This construction is not a detriment to forward impulsion for a sprinter, but a horse with this conformation will usually tire if he tries to maintain high speed for very long.

For best speed and stamina, the humerus should not be too horizontal or it will cramp the movement of the elbows and the swing of the leg. The angle between it and shoulder blade should be the same as the angle in the hindquarters between pelvis and femur. A long, well sloped shoulder is generally accompanied by a relatively upright humerus, whereas a steep, short shoulder usually goes hand in hand with a longer and more horizontal humerus.

Forearm

The forearm, between elbow and knee, should be long, wide and thick, with well-developed muscles. These muscles are important for speed, and should be large at the top and slimmer at the bottom as they taper to tendons at the knee. For endurance, the muscles should be smooth and long, rather than bunched up and short. For speed, the forearm should be relatively long (since it contains the muscles) and the cannon bone relatively short.

Length from shoulder to knee

The forearm, between elbow and knee, should be long, wide and thick, with well-developed muscles. Also, look for larger muscles at the top that taper to the tendons at the knee.

A long forearm allows for longer muscles and shorter tendons, creating better leverage action for moving the leg quickly and with less clumsiness. The longer the forearm, the greater the arc it can make (longer stride). If the forearm is short, it must make more total movements in the same amount of time, but the strides are shorter and the horse must work harder--moving his legs faster--in order to keep up the speed.

Knees

This joint should be large, flat at the front, and well proportioned. A small, pinched-in knee crowds the tendons and joint cartilages and hinders free action. A knee too small also increases the effects of concussion. A flat front gives a smooth surface for the extensor tendons to glide over as they straighten the leg at each stride.

The knee should be directly in line with the forearm above and cannon bone below. If the cannon is set too far back, rather than centrally located under the knee, the horse is calf-kneed (back at the knees); the front of the leg looks concave when viewed from the side.

More strain is thrown onto the tendons at each stride, which can lead to injury if the horse is used hard. This structure also creates more concussion, and over-extension of the joint (bent toward the rear), puts the horse at risk for carpal fractures.

The opposite fault is over-at-the knees (also called buck knees, goat knees or sprung knees), with the leg looking slightly bent forward at the knee. This can be an inherited conformation, or due to overwork--with injury to the check ligament or too much stress on the structures at the back of the knee. A severely buck-kneed horse is prone to stumbling because the knees more readily give and buckle forward.

A horse that is out-at-the-knees (bowlegged when viewed from the front--carpal varus) often has base narrow, pigeon toed conformation. This puts extra strain on the outside ligament of the knee, the inside portion of the knee bones, and outside portion of the joint capsule. A horse that is in-at-the-knees (carpal valgus, or knock kneed) has knees too close together. The lower leg may angle outward in a splay-footed stance, putting strain on the leg and joints in the opposite direction.

Other deviations from good leg conformation, when viewed from the side, include tied-in-at-the-knee, with the flexor tendon too close to the cannon bone just behind and below the knee, inhibiting free movement. This indentation usually means the tendons are too small and not as strong as they should be. The leverage ability of the muscles above the knee is decreased, since the tendons are pulling inward against the back of the knee instead of having a straight pull down the back of the leg.

Cannons

The cannon bone between knee and fetlock joint has a smaller splint bone on each side, toward the back. The cannon bone should be perfectly straight up and down when viewed from front, side or rear. Muscles in the forearm continue downward (below the knee) as long tendons--in front and behind the cannon bone--to flex or extend the lower leg.

An athletic horse has long forearms and relatively short front cannons for best leverage. If the cannon and associated tendons are too long, there is more stress on the tendons and they are more likely to be injured. The horse's leg muscles will also tire more quickly when doing hard work because there is less muscle (forearm) to do the work and more weight (cannon bone) to the lower leg.

The cannon should be wide when viewed from the side, rather than small and round. A lower leg with good flat bone has a lot of depth from front to back; this term describes a combination of bone and tendon, with the tendon set well back of the cannon bone rather than right next to it. If the tendon and bone are too close together (âroundâ bone) there is too much friction between the moving parts. The leg won't hold up as well.

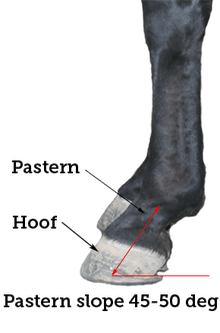

Fetlock joint and pastern

The joint between cannon and pastern should be broad from all angles--rounded a little at the front but firm and flat on all sides. The joint should be in line with the cannon above and pastern below it. Pasterns should slope moderately, with adequate length to give and dissipate concussion.

Too much slope, however, puts too much pressure (from tendons and ligaments) on the sesamoid bones at the back of the fetlock joint and makes a weak pastern that may go clear to the ground when the horse tires during exertion. If it doesn't slope enough, the horse will have a choppy, jarring gait and the increased concussion will damage his feet and legs.

A too-long pastern reduces potential for speed because it takes longer to push off at each step to get the foot off the ground. A too-short pastern is almost always too upright, creating a pile-driving pounding effect. A good rule of thumb is that a pastern is too short if it is less than half the length of the cannon bone, increasing the risk for concussion injury and also creating a shortened stride.

Many horsemen feel that a short pastern is an advantage for propulsion (especially for fast starts) but it must slope enough to absorb concussion. A horse can usually manage fairly well with pasterns that are short and sloping or long and steep. But the opposite combinations (short and steep, or long and sloping) generally cause trouble.

Sidebar: Dissipating concussion

The impact of the foot hitting the ground at fast gaits is offset by the way a good foreleg is structured and how it moves--distributing the force so that no one part suffers more stress than any other.

The more nearly ideal the leg and joint conformation, the more uniformly the trauma of concussion is distributed. Movement within the compound joints of the knee (two rows of small bones between forearm and cannon), the pumping action of the foot (with the blood-filled plantar cushion acting as a shock-absorbing buffer, similar to that of a gel-filled sole of a human athletic shoe), and the springy give of a properly sloped pastern are the main shock-absorbing factors in the front leg.

The action of the pastern transfers some of the strain away from the leg bones and onto the tendons--and hence to the more elastic muscles of the upper leg. The shoulder blade glides over the ribs, transferring any remaining shock (not taken up by the pasterns) to the body.

If all the bones of the front leg were in a straight line like a pipe--with no shoulder or pastern slope--concussion from each step would go directly from the ground to the body. But with proper angles in the foot, pastern and shoulder, most of this jarring stress is dissipated on the way up.

Third in the series

This is the third in a series of five articles that are written by the author of "The Horse Conformation Handbook

." This book, illustrated by Jo Rissanan (a frequent EquiMed contributor), is a must read for anyone interested in a detailed understanding of horse conformation.

Previous Horse Conformation - Head Neck and Shoulder

Next in the series Horse Conformation - Importance of Proper Hind Leg Conformation.