The scandal over horse meat in the European food chain has widened from a case of mislabeling to one of food safety as public health authorities in Britain said that a powerful equine painkiller, potentially harmful to human health, may have entered the food chain” in France.

Powerful painkiller in horses

The scandal over horse meat widened from a case of mislabeling to one of food safety as a powerful equine painkiller, bute, potentially harmful to human health, may have entered the food chain in France.

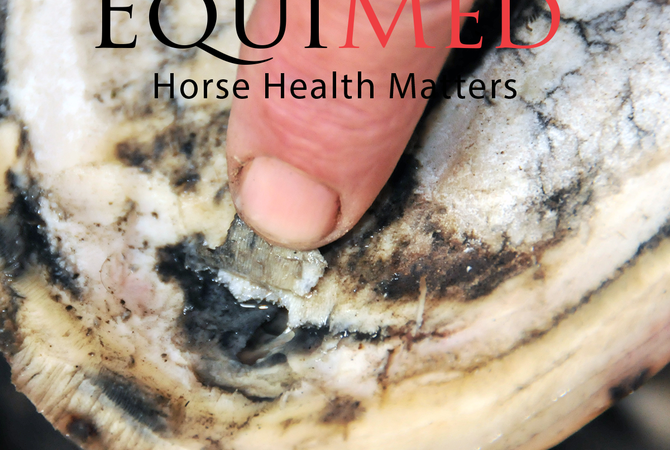

British officials sought to reassure the public that the drug — phenylbutazone, or bute, an anti-inflammatory used commonly on lame horses — was found only in trace amounts in a small number of British horse carcasses. Out of 206 carcasses, 8 tested positive for bute, and just 6 of those carcasses were exported to France.

The drug is also used to treat arthritis in humans. Very large doses can cause a potentially fatal blood disorder, aplastic anemia, in which the bone marrow fails to produce enough blood cells.

Even before the discovery, the scandal had plunged the European food industry into crisis. Frozen foods, including hamburger, lasagna, spaghetti Bolognese and moussaka, have been withdrawn from supermarket freezers in Britain, Ireland, Sweden, France and Germany.

But the positive tests for the equine drug have raised new concerns, even in countries like France, where eating horse meat is more acceptable than in Britain, where it is taboo. Unlike cattle, which are raised for slaughter in controlled conditions, the lame horses or former plow animals that are sometimes killed for consumption do not carry the same guarantees of origin or quality.

“Unscrupulous criminal elements have been profiting from these unfortunate animals by exploiting a hopelessly flawed horse passport scheme, lax animal export controls at ports, and slaughterhouses willing to compromise animal welfare and public safety for a quick profit,” said David Wilson, the spokesman for the Ulster Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, in Northern Ireland. The discovery of suspect frozen beef hamburgers in Ireland set off the crisis.

“Many horses that are either valueless or in suffering are being corralled in remote farmyards and packed into vehicles for transport to abattoirs in Ireland and the U.K.,” he said. “After slaughter, many are processed and find their way effortlessly into the European food chain.”

Health experts said that a human would have to eat 500 or 600 burgers a day of 100 percent horse meat to be adversely affected by the drug at the level found in the carcasses.

The police investigating allegations that horse meat was mislabeled as beef said Thursday that they had arrested two men in Wales and another man in West Yorkshire, England, on Tuesday and were holding them on suspicion of fraud.

Checking food safety “from farm to fork” in Europe has been a persistent worry for two decades, since the crisis of mad cow disease in Britain threw the Continent into a crisis and prompted a ban on British beef exports to Europe and the United States.

The current scandal has a supply chain for meat so murky and complex that officials and experts say it is easily susceptible to fraud and manipulation by organized crime. The convoluted route from slaughterhouse to plate has highlighted a weak system of accountability in a vast single market of almost 500 million people, where retailers use layers of meat traders to find the cheapest deals and no regular tests are conducted to authenticate meat products.

“In a cash-rich business like the meat industry, there is ample opportunity for criminals to bribe bureaucrats,” said Misha Glenny, an expert on organized crime in Europe. “Market opportunities create criminal opportunities."