Colic is the #1 emergency seen by horse owners, trainers, and veterinarians. Signs of colic can range from subtle changes only an owner would notice to severe demonstrations of pain and distress. Because early treatment is the key to success, it is important that you understand the clinical signs of colic, how to recognize them, and what you can do to help your horse while waiting for the vet to arrive.

Colic is the #1 emergency seen by horse owners, trainers, and veterinarians. Signs of colic can range from subtle changes only an owner would notice to severe demonstrations of pain and distress. Because early treatment is the key to success, it is important that you understand the clinical signs of colic, how to recognize them, and what you can do to help your horse while waiting for the vet to arrive.

What is colic?

The first thing to understand about colic is what the word really means.

Colic is not a disease but a symptom of a disease. By definition, the term "colic" is the manifestation of abdominal pain. For the most part, this means a problem with the GI tract, somewhere in the 100 feet of intestine between the stomach and the rectum.

Gut sounds are an important clue regarding colic

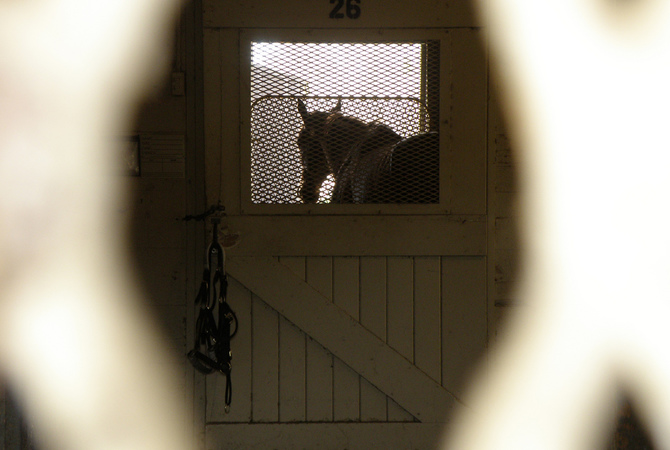

Experienced horse owners quickly recognize colic through observation and monitoring of vital signs.

While the vast majority of cases of colic have to do with intestinal distress, there are a handful of other organs within the abdominal cavity that can cause pain and colic-like symptoms. These include the spleen, kidneys, the ovaries and uterus (for mares), the bladder, or even the lining of the abdomen (aka the peritoneum).

Horses can also occasionally display colic-like behavior due to an extra-abdominal disease such as pneumonia, if it is painful to breathe, or neurologic disease, where some signs could be mistaken for colic. So even though an intestinal problem should be first on your list, it is also important to keep an open mind when evaluating and diagnosing a horse that is colicky.

Clinical signs of colic

The most common overt clinical signs include the following:

- Pawing

- Rolling

- Flank-watching (looking back at their belly as if to say "This is where it hurts!")

- Laying down or attempting to lay down

- Kicking at the abdomen

- Stretching out

- A distended abdomen

- Poor appetite or complete anorexia

- Decreased or absent manure production

More subtle or less common signs can include:

- Depression

- Increased respiratory rate (often with flared nostrils)

- Flehmen (curling the upper lip up) - this is especially true in mares with urogenital pain

- Playing in the water bucket (without actually drinking)

- Holding head and neck out in an odd position

- Sweating (when they have no reason to)

- Grinding their teeth (specifically indicative of gastric ulcers)

Horses will have changes in their vital signs and it is important to know what is normal for all horses (and what is normal for your horse) in order to spot the irregularities. The most common abnormality is an increased heart rate.

The heart rate can be increased due to pain anywhere in the abdomen or dehydration, and tachycardia has also been linked to a distended stomach.

Because a horse cannot vomit, as fluid or feed backs up into the stomach, it becomes distended. The more distended, the higher the heart rate. A horse with a heart rate greater than 60 bpm should have his stomach checked with a nasogastric tube for excess fluid, called reflux.

The respiratory rate can be normal, but is often increased due to pain or distension of the abdomen pressing on the diaphragm. Often the rectal temperature is normal, but in cases of severe dehydration and shock a low reading can be obtained.

Alternatively, if there is significant disease in the bowel and a brewing infection or septic process, a fever may be detected. The color of the mucous membranes (gums) should be evaluated. Normal horses have pink and moist gums, but as a colicky horse becomes dehydrated his gums can become dry and tacky. Horses who are developing a septic abdomen from a compromised bowel can have bright red, brick red, or even purple mucous membranes as a sign of septic shock.

The capillary refill time (CRT) is recorded by pressing a finger firmly on the gum line so that a white blanched fingerprint is left. The CRT is the time it takes for the normal pink color to return to that spot. Dehydrated horses have a delayed CRT and this is one of the most accurate estimations of hydration on physical examination of a horse.

GI sounds, also known as borborygmi, can be heard by listening to the horse's abdomen in four designated quadrants; upper right and left (just in front of the point of the hip, what we call the paralumbar fossa) and the lower right and left (on the curve of the belly just in front of the stifle).

Horses should have audible, occasional gurgling and rumbling at all four sites. Many colicky horses with GI disease have decreased borborygmi, and the complete absence of GI sounds is indicative of a more severe problem.

| Clinical signs used to diagnose colic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Clinical signs | Normal | Colic |

| Heart rate | 36-44 beats per minute | >60 beats per minute |

| Respiratory rate | 10-16 respirations/minute | May be elevated |

| Temperature | 99-101.5°F | May be elevated |

| GI sounds | Gurgling in all 4 quadrants | One or more quadrants with minimal or no gurgling |

| Mucous membranes | Pink and moist | Pale, or bright red to purple |

| Capillary refill time | 1-2 seconds | >2.5 seconds |

Colic calls for quick action - but don't panic

Once you have recognized an episode of colic, it is most important to stay calm and assess the situation. Write down the horse's behavior and vital signs so you can track his progress and give the veterinarian the most accurate description of the situation over the phone.

You should also be able to tell your vet about any recent changes in diet or exercise and your current vaccine and deworming protocols. Remove all hay and feed from the horse, as most conditions will be worsened by additional feed in the GI tract.

Allowing access to water is fine, unless the horse is so violently thrashing that the water bucket itself poses a threat. If the horse is this distressed, carefully attempt to move him to a safe location where he cannot traumatize himself and, just as importantly, hurt any people who are trying to help.

Hand walking a colicky horse can distract him from the discomfort and may help with GI movement, but take care not to overdo it. Excessive walking can cause a horse to become fatigued or exhausted and certain conditions that may look similar to colic (like Botulism or tying-up) can actually be worsened by forced exercise.

Owners are often confused about what to do if a horse lies down or tries to roll. Equestrian folklore tells us that if a colicky horse rolls, his intestines will twist. This is not the case. Horses roll because they are in pain (possibly due to twisted intestines), but rolling does not cause colic.

We do recommend preventing a horse from rolling, but this is to prevent self-trauma that can be sustained to the head, eyes, and legs as he thrashes. If a horse is laying comfortably, it is fine to let him be, and if a horse is rolling so vigorously that you can't get close enough to help, then keep yourself safe and wait for the vet to arrive.

Keep your veterinarian informed - just in case

While a veterinary visit is not necessary for every episode of colic, it is a good idea to contact your vet and let them know what is happening. They may be able to deduce the severity of the situation from the excellent description of behavior and vital signs that you provide and help decide if an emergency call is needed.

They will also be able to advise you on medications that you can administer to lower inflammation and ease the pain. Flunixin meglumine (Banamine®) is the most commonly used anti-inflammatory in colic cases. The dose and route of administration depends on what product you have (paste or injectable), your level of comfort with administering medications, and your horse's bodyweight.

Make sure you record what, how much, and when the drug is given so that you have an accurate record to help guide further treatment.

Colic in the horse can be sudden, frightening, and confusing and if you work with horses long enough you are bound to encounter an episode or two. But as long as you are attentive to your horse's actions and aware of the clinical signs, you can administer timely treatment that can preserve the health of your horse.