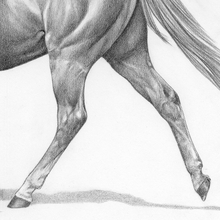

Conformation and a horse's legs

A horse with good conformation is going to have well-formed, symmetrical legs. When the horse is viewed from the front, the observer can drop an imaginary line from the top center of the leg at chest level down through the forearm, knee, cannon, and fetlock to the center bottom of the hoof. When viewed from the side, the center line will split the leg to the level of the fetlock and then fall to the ground, just behind the heel.

A horses's leg conformation is critical to performance and survival

In the wild, a horse's life depends on being capable of out-running predators. Good breeders focus on leg conformation to improve with each breeding.

When the hind leg is viewed from behind, the imaginary line will run from the back of the hindquarters along the back of the gaskin, hock, cannon, fetlock, and pastern to the bulbs of the heels. Viewed from the side, the straight line will run downward from the back of the buttock, and touch the back of the hock, cannon, and fetlock.

A horse with proper leg angles has less stress on its joints, and the legs are better able to absorb the concussion from the impact of each hoof as it hits the ground.

The front legs of the horse carry approximately 60 percent of the weight of the horse and are constantly subject to lameness with approximately 95 percent of lameness occurring from the knee down, with the foot being the site of most problems.

The hind limbs are involved in approximately 20 percent of cases, with the hock and stifle joints being the main problem areas.

Since a horse's legs are made up of a finely tuned system of bones and joints, ligaments and tendons, muscles and connective tissue designed to carry a relatively heavy body, good conformation coupled with healthy limbs is extremely important for proper function.

Important parts of the horse's forelimbs

The horse does not have a collarbone, so the front legs are not attached by joints, but rather to a sling of muscles and ligaments that support the weight of the horse and rider. The shoulder blade, or scapula, is connected to the spine by muscle and ligaments and allows freedom of movement and absorption of concussion.

The humerus is the upper end form point of the shoulder and connects the shoulder blade to the forelimbs. The upper part of the foreleg consists of the ulna, a short bone that forms the point of the elbow, and the radius, which is a long bone that stretches to the knee joint.

The knee joint, or carpus, is composed of the carpal bones and allows movement in the foreleg. The cannon bone is a weight-bearing bone in the lower leg and stretches from the knee joint to the fetlock joint. On either side of the cannon bone are the splints that help support the carpus bones of the knee.

Behind the fetlock joint are two bones known as the sesamoids. These bones provide a groove to hold the tendons of the leg, which act as a pulley system for movement of the lower leg.

The pastern bones occur above and below the pastern joint with the long pastern on top, between the fetlock and the joint, and the short pastern below the joint connecting to the coffin joint.

The pedal bone is a hoof-shaped structure in the foot that serves for the attachment of tendons and ligaments from the muscles in the forearm. The pedal bone, also known as the coffin bone or P3, is the main bone in the foot.

The navicular bone is a small bone located behind the pedal bone. The navicular bone functions as a pully for the deep flexor tendon that wraps around the navicular and is attached to the pedal bone.

The horse's hind limbs

The top part of the hind limbs consists of three fused bones, called the ileum, ischium, and pubis. The ischium forms the point of the buttock. They are joined to the spine through the sacroileac joints and allow transfer of propulsion to the hind legs.

A horses's hind legs

The power propulsion system and major defensive tool, a horse's rear legs are functional and beautifulNew window.

The pelvis or pelvic girdle serves to protect the inner organs, including the uterus. The femur, which is a large bone, connects with the pelvis at the hip joint and with the hind leg at the stifle joint. The tibia forms the upper part of the hind limb from the stifle to the hock. The fibula is a smaller bone that extends half the length of the tibia and sits parallel to it.

The patella, or kneecap, is the bone in the stifle joint above the fibula and tibia. The hock joint allows movement of the hind leg and consists of the tarsus bones, the tuber, and the calcaneus at the back, which forms the point of the hock. Below the hock joint are the hind cannon with splint bones, the long and short pastern, the coffin joint and bone, the sesamoid bones, and the pedal and navicular bones similar to those in the front limb.

Horse legs as an "apparatus"

- Apparatus:

- a set of equipment for a particular use; a complex machine or device.

The legs of a horse are made up of a system of various apparatuses composed of muscles, ligaments, tendons, and connective tissue that work together to support the horse as it stands and to diminish compression during movement, thereby protecting the horse from injuries to its limbs.

One of the main apparatuses is known as the stay apparatus and is made up of several components: the check apparatus, the reciprocal apparatus of the hind limb, the suspensory apparatus of the fetlock, and the suspensory ligament.

The check apparatus allows a horse to sleep standing on its feet by locking the lower legs without much muscular effort.

The reciprocal apparatus of the hind limb aids in preventing fatigue when the horse is standing and insures that there will be reciprocal flexing of the hock joint when the stifle joint is flexed or that the hock will extend when the stifle extends, thereby preventing injuries.

The suspensory apparatus of the fetlock absorbs the shock of concussion and supports the fetlock, which is the joint subject to the greatest stress. The suspensory apparatus is composed of the suspensory ligament, the paired sesamoid bones and ligaments, and the superficial and deep flexor tendons.

The suspensory ligament serves to cushion impact and prevent extreme overextension of the fetlock joint. This ligament is a wide, elastic, tendon-like band that runs from the back of the cannon bone and attaches to the back of the upper third of the long pastern bone. This ligament divides into two branches that surround and partly encase the two proximal sesamoid bones. They also join the common digital extensor tendon where the two branches attach to the long pastern bone.

In addition to the ligaments, the tendons, which are a tough, non-elastic band of fibers, connect the muscles to the bones. Tendons serve as either flexors or extensors, depending on whether they bend the limb or straighten it.

The digital extensor is the large tendon that runs down the front of the horse's leg. It straightens the leg and extends the fetlock, pastern, and coffin joints. The superficial digital flexor tendon runs down the back of each leg and forms the rear outline of the leg. Beneath the superficial tendon is the deep digital flexor. These two tendons combine to flex the knee and all the joints below. In the hind limbs, the flexors also straighten the hock.

Looking at a structurally sound horse, it is important to note that the horse has no muscles in its legs below the knees and hock. The lower part of the leg is made up of bone, tendon, ligaments, cartilage, skin and hair. For this reason, a great deal of consideration needs to be given to making sure that the legs of the horse are scrutinized regularly so that any predisposition to unsoundness or injuries can be treated properly, thereby preventing lameness.

Since the form of the horse's legs is closely associated with the function, it is not an overstatement to stress their importance in the overall well-being of the horse.

All in all, form meets function in the legs of the horse, combining purpose, strength, and beauty.

Dig deeperTM

Learn equine anatomy terms by visiting the Equine Anatomy Project.