For most mares, births are normal; the mare breaks her water, lies down, and almost immediately the foal’s front feet appear, then the head. With a few hard contractions, the mare moves him on out through the birth canal. This results when the horse fetus is properly positioned in the uterus before birth.

Occasionally, however, the foal is too large, or not presented correctly, and can’t be born without assistance. Studies indicate that approximately 1 in 10 equine births have an abnormality, called dystocia. Horse breeders must be aware of the danger of dystocia and be prepared to help the mare during birth. An equine veterinarian should be notified and on-call whenever a birth is expected. In some cases, the life of the foal and the mare are both endangered and surgical intervention will be required!

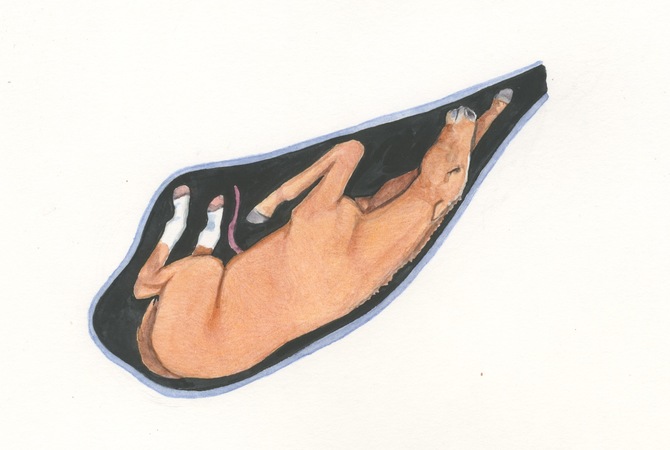

Normal presentation

The majority of foalings proceed quickly, and without problem when the foal is positioned as illustrated above.

© 2020 by JoAnne Rissanen New window.

In these instances, the mare needs help, or the foal will die--and the mare’s life may also be at risk. A serious malpresentation will require a veterinarian.

What to do while waiting for the veterinarian

Get the mare up, if possible, to keep her from straining hard until help arrives. If it’s a simple problem, and you are not sure how soon the veterinarian will arrive, try to correct it yourself. Even if it’s serious you may have to try to help the mare while you wait. Unless help comes soon, malpresentation will result in a dead foal.

Have the mare’s tail bandaged, her genital area washed with mild disinfectant and warm water, and use obstetrical sleeves or very clean hands. Use lots of lubricant (K-Y jelly works) on your arm or OB sleeve when you carefully reach in to check the foal’s position. Have someone hold the mare for you if she is up. If she is down, you may be able to slip up behind her and check, without disturbing her.

One foot turned back

If only one front foot appears, reach in to see if the other is close enough to grasp and straighten. If it is close but you cannot pull it out, get the mare up and push the first leg back in a bit while you pull on the missing one. If you cannot find the missing leg (just the nose), it may be turned back clear at the shoulder, which will be very difficult. If you cannot get help quickly, push the foal back into the uterus and try to reach farther in to find the missing leg. The mare’s straining will make it hard, so you’ll need her on her feet and someone holding her.

Be very careful when trying to manipulate the foal; the uterus can be torn by a foot or nose pushing hard in the wrong place. If you can get hold of the missing foot, cup it in your hand so it won’t tear the uterus, and bring it inward and upward--under the foal’s neck and over the pelvic brim. Once you have both legs in the birth canal and the head in proper position, you can pull on the legs. Make sure the nose is coming through the birth canal, and that by bringing up the missing leg you have not pushed the head back too far.

Nose, but no feet

Sometimes only the nose appears, with both legs turned back. This often means the foal is dead; a live foal squirms and gets his legs aimed into the birth canal during the mare’s early contractions, but a dead foal is limp and may not position properly. The head-first, legs-back position is often typical of a dead twin. The second one might be alive, so get help.

Head turned back

If both feet protrude, but no head, this can be difficult to correct. Attempts should be made only if your vet is unable to get there quickly. If you must try it yourself, lubricate both arms to your shoulders. The mare must be on her feet. Push the foal back into the uterus with one hand and try to find the head with the other. This may take more strength than you have, especially if the mare is straining and working against you, but unless your veterinarian gets there quickly, you have to try. The foal’s head may be down between the legs or off to one side. If you can get hold of the lower jaw you may be able to pull the head up into position. Even if you are eventually able to get the head up and the foal delivered, it may be dead by that time.

Any birth that takes more than 30 minutes can result in a dead foal, because the placenta begins to detach. The foal may die before you get him out, even if you correct the malpresentation. Even if the foal dies, you must still get him out to save the mare, so try to stay as clean as possible and be careful not to damage her.

Make sure they are front feet

If you don’t see the nose, check to make sure the protruding feet are fronts. Fronts have soles down; hind feet are pointed upward. Even if they are pointed up and you think they are hinds, check. Reach in alongside the leg to see if you have knees or hocks. The foal may be frontward but upside down, or sideways. If the foal is upside down with head turned back, you have a serious problem, but if the head is there the foal just needs to be turned over. This may happen naturally if the mare gets up and down a few times; often in early labor she gets up and down a lot, helping the foal rotate into proper position.

Backward foal

If hind feet are in normal posterior position, the foal can be born, but birth must be accomplished quickly or he will suffocate or draw fluid into his airways before he is out of the birth canal. If, when you reach in to check, you find hocks instead of knees, and the veterinarian has not yet arrived, keep the mare on her feet and try to keep her from straining until the vet comes.

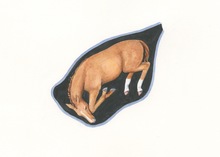

Posterior presentation

This posterior presentation has a complicating factor. One hind leg is positioned forward. The delicate operation of repositioning the forward leg requires skill and care to avoid damage to the uterus.

© 2020 by JoAnne Rissanen New window.

If the mare strains anyway, moving the foal through the birth canal, have someone help you pull on the foal. The mare might be able to deliver the foal herself, but it will die without help, because she will stop to rest a few times during the birth (as when the foal’s hips are passing). The umbilical cord will be broken off too soon, or compressed by the foal’s ribcage. With his oxygen supply cut off, the foal must start breathing.

If there are at least 2 people to pull, you may get him out alive. Put obstetrical chains or straps above fetlock joints of the hind legs, and when the mare strains, pull with all your strength--one person on each leg. Never put chains, straps or ropes around the pasterns or you may injure the joints. As the hips emerge, keep pulling, even when the mare stops to rest. The foal must come out immediately, or he will die.

If the mare is standing when you pull the foal, catch him to break his fall. Get him breathing. He may be limp and unconscious due to lack of oxygen. Clear away any mucus from his nostrils with a suction bulb if you have one.

Breech foal

Breech presentation is much more difficult than a normal backward birth. The breech foal has hind legs forward, in sitting position. Nothing will enter the birth canal; the rump is jammed against the cervix. The mare seems to be in labor, but there is no progress. You may think she’s still in early labor, and may not check her in time--in which case the foal will die.

Breech presentation

A breech presentation is one of the most difficult to resolve, and has the potentially of death for both mare and foal. Call your veterinarian immediately if you suspect a breech presentation.

© 2020 by JoAnne Rissanen New window.

If you become suspicious that something is wrong, have someone hold her for you while you check. When you reach into the birth canal, there will be nothing there; if you reach to the cervix you will feel the foal’s tail or rump. A breech presentation is difficult, even for a veterinarian (to push the foal deeper into the uterus and try to get each hind leg up over the pelvis), and the foal may have to be delivered by Caesarean section.

Any malpresentation is best handled by an equine veterinarian, but time is crucial. You may on some occasion have to try on your own--if the veterinarian has not arrived or is not available. If you wait and do nothing, you will have a dead foal, and possibly a dead mare.

Placenta coming first

This situation requires fast action to save the foal. If the mare starts second stage labor and you see a thick mass of dark red membrane coming, instead of the clear white amnion sac (with the foal’s feet inside it), scrub up and break through the thick red membrane. Reach into the birth canal and get hold of the legs and pull the foal out swiftly. His lifeline is detaching from the uterus, and the sooner you get him out, the better.

Get the foal breathing

If a foal doesn’t start breathing as soon as he’s born, tickle the inside of his nostril with a piece of clean straw or hay to make him cough and sneeze. If that doesn’t work, slap his ribcage. If he still won’t start, lie him on his side with head and neck extended. Cover one nostril tightly with your hand, holding the mouth shut, then gently blow into the other nostril until the chest wall rises to show the lungs are filling. Let the air come back out. Repeat this until the foal starts breathing. As long as there’s a heartbeat, there’s hope. Check for heartbeat by feeling the left side of the ribcage, just behind the elbow.