According to an Equine Science Up-date, archeologists led by Professor Eliezer Oren from Ben Gurion University have excavated an equid burial at Tel-Haror, an archeological site with strata dating to the Middle Bronze IIB Period (1,750-1,650 B.C.). Among the bones they found a metal equestrian bit.

New evidence of usefulness of donkeys

The donkey burial at Tel Haror is special since it provides the earliest direct evidence of a metal equestrian bit.

Dr. Joel Klenck, a Harvard University educated archeologist and president of the Paleontological Research Corporation specializes in the analysis of animal remains. He identified the equid as a donkey by the shape and size of its pedal bones and traits on the grinding surfaces of its teeth.

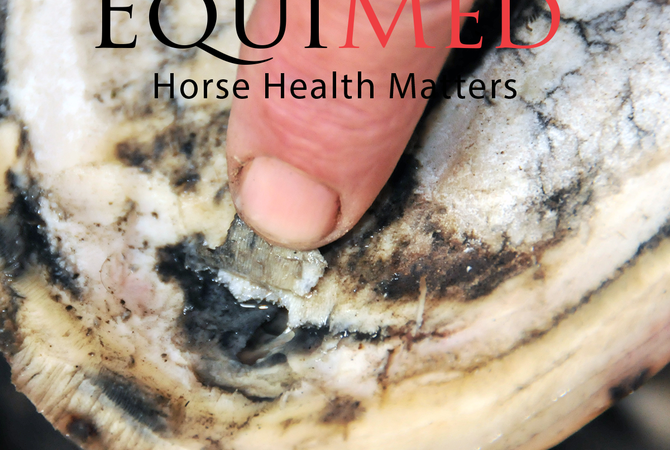

Klenck points out that the donkey burial at Tel Haror is special since it provides the earliest direct evidence of a metal equestrian bit. He states, “Until the excavation at Tel Haror, archeologists had only indirect evidence for the use of bits. An example of this indirect evidence is wear marks on equid teeth at the fortress of Buhen in contexts dating to the twentieth century B.C. At Tel Haror, we retrieved the actual metal device.”

He notes the ancient bit caused equids to turn due to the force of the device. Also, round plates on either end of the ancient bit exhibit triangular spikes that pressured the lips if the reins were pulled from one direction.