Strict enforcement of a state equine health regulation at the weekly Camelot horse auction in Cranbury has raised fears among rescue groups, concerned the situation could mean more animals going to slaughter.

For nearly two years, the groups and individuals -- many of which post on the Camelot Horse Weekly page on Facebook -- have been instrumental in networking to save horses coming up for sale at Camelot from the "killer pen."

Since the last U.S. horse slaughterhouse closed in 2007, American horses destined for slaughter are shipped under problematical conditions to Canada or Mexico for a cruel end, so their meat can be sent overseas.

Rescue groups try to prevent that outcome for the Camelot horses, but they feel the recent enforcement effort means some sale horses appear to be going elsewhere, out of reach of both the state and their would-be rescuers.

Camelot, which was closed by the state for two weeks in July, has been operating on temporary permits since then.

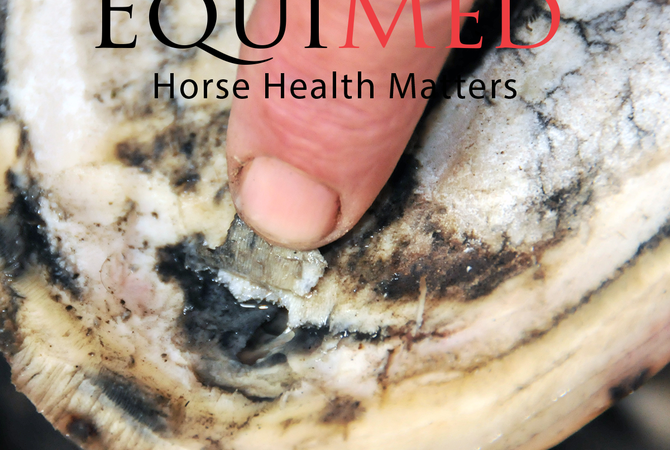

The state has taken issue with owner Frank Carper for failure to have Coggins tests (to detect incurable Equine Infectious Anemia) on horses within 90 days before they were sold. Many horse owners are unaware of the provision that anyone who transfers ownership of an equine in New Jersey must have a Coggins no more than 90 days beforehand, unless the animal is going directly to slaughter. Horses being transported in the state are required to have a negative Coggins every two years, while horses imported from another state or another country must have had a negative test within 12 months.

Carper had been bringing horses over from a New Holland, Pa., auction and having them tested when they arrived in New Jersey. At the behest of the state, that procedure was changed in March.

Carper's wife, Monica, said "because we're trying to maintain a decent relationship with the department," her husband now obtains the 90-day Coggins and health certificates in Pennsylvania before bringing them into New Jersey.

"The conversations with Camelot regarding the need to follow the state’s animal-health laws and regulations began well before this past March," commented a state spokesman.

"The matter of repercussions for violations of those laws and regulations is still a matter to be determined. The Department’s primary interest is to ensure compliance with all animal health laws and regulations in New Jersey."

EIA, also known as swamp fever, is a viral disease that has been compared to HIV in humans. It is spread by blood-to-blood transmission, usually involving insects. Animals testing positive either must be isolated or destroyed.

With the economic downturn, the unwanted horse problem has increased exponentially. Horses often wind up at auctions, where leftovers go to the "killers," because their owners simply can't afford to keep them and are unable to sell them privately in a saturated market.

After the state crackdown on Camelot, horses lacking 90-day Coggins that are brought in by private owners either have to be turned away "and there are a lot of situations where they cannot take it home," said Monica Carper, "or B, the only other option left open to us by the law now is that the horse has to go directly to slaughter."

"It's all about the 90-day Coggins," she maintained. "People call on the phone and when I tell them they have to have it, they say, `I can't afford to do that' or `the horse isn't worth that' or `I have to sell it now' and they just never show up." She believes some of the horses may instead be put on Craigslist or other websites, or are going to New Holland and wind up not having a Coggins test at all.

Horses often come to the auction because their owners are desperate; they have lost their jobs or the cost of horsekeeping has risen beyond their means.

Carper notes "people are trying to do right by their horse and not starve it to death in their backyard, but they can't spend another $100 for the test."

The state spokesman said the Division of Animal Health's cost for the Coggins is $4. A barn call for a veterinarian to take the blood makes it more expensive, but he noted, "We do not have legal authority to dictate to them what to charge."

Another spokesman said the Department of Agriculture believes the cost of the test "will not mean the horses will change destination from sale to a new owner to slaughter."

"I share the compassionate concern for horses and their rescue," state Secretary of Agriculture Douglas Fisher said in a statement, noting, 'we hope the number of horses without homes will decrease."

At the same time, he observed, "These rules exist for a reason -- the horses...if New Jersey lets its guard down and `looks the other way,' we would be complicit in endangering them."

The state spokesman explained, however, "Licensed livestock dealers have the obligation to follow the laws and regulations of the State of New Jersey. One of those regulations is that a licensed livestock dealer cannot sell a horse that has not presented a negative Coggins test result within 90 days prior to a sale."

He anticipates that Camelot will be granted its annual license "when the pending issues are resolved."