The 64th running of the Tevis Cup (aka Western States Endurance Ride) gets underway on Saturday, August 17. This is one of the best-known endurance rides in the world, and attracts riders from all corners of the U.S. and around the world to follow 100 miles of single-track trail from Robie Park, outside of Truckee, California, to Auburn, California, known as the “Endurance Capital of the World.”

Horses and riders on endurance trail

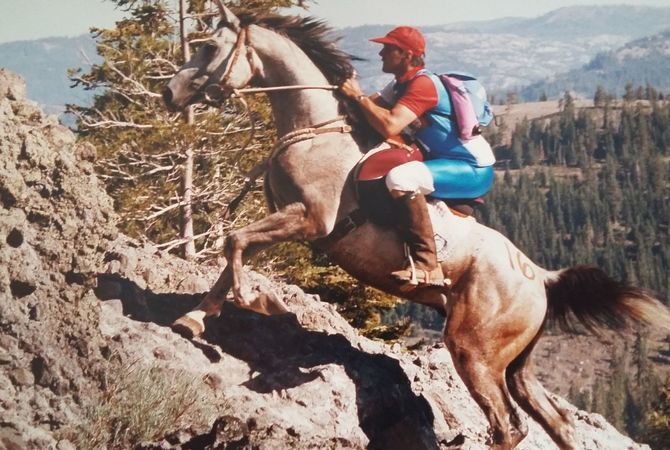

The Western States Trail Ride, "Tevis," covers 100 miles of the famous Western States and Immigrant Trails over the Sierra Nevada MountainsThe Western States Trail Ride, "Tevis," covers 100 miles of the famous Western States and Immigrant Trails over the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

© 2016 by Andrey Lebedev

It is sanctioned by the American Endurance Ride Conference, headquartered in Auburn, just a stone’s throw from the ride’s finish line.

Among those attempting the grueling test of equestrian skill will be Bruce Weary, DC, of Prescott, Arizona, whose mount this year is an 11-year-old Standardbred gelding named Trooper. Bruce has a history with the Tevis Cup ride: he’s attempted it multiple times, and has only completed the ride once, in 2009, with John Henry, a Tennessee Walker owned by Susan Garlinghouse, DVM.

Let’s let Bruce tell the story:

In anticipation of the annual of the Tevis Cup, aka Western States Trail Ride, I was asked to share some thoughts about my experiences with this ride, what it means to me, and what it might mean to those who dream of swingin’ a leg over a good horse and meeting the Tevis trail head-on.

I’m not sure if being asked to do so was a compliment or not. You see, it took me 15 years and seven attempts to finish this ride—just once. Compared to the efforts of some select riders who have collected a couple dozen buckles or more, I might just as well be the poster child for how not to conquer the Tevis trail.

My first attempt was in 1994, on a grade horse named Thor who had a few hundred miles on him. I had heard of this 100-mile ride in the Sierras, and I decided we’d take a shot at it—with two weeks of preparation. I worked him on some steep hills a few times, put new shoes on him, and figured we were ready.

I planned to get off and lead Thor any time I came to a hill, just to help him out a little. I tried that all the way to Robinson Flat and, upon my arrival, I promptly told my crew, “I wish to die now. Please kill me.”

I had never been so exhausted in my life. With fluids and food I regained some strength, however, and the Mighty Thor, as he was affectionately known, dragged me onward—through Dusty Corners, Last Chance, Deadwood, Michigan Bluff, and the hot, steep canyons that link them together.

Thor literally learned to tail at the bottom of the first canyon, and did it like he had known how all his life.

On reaching Michigan Bluff, I silently prayed that the control judges would find something wrong with Thor, that this madness might end. “You’re good to go!” bellowed the vet who examined Thor. Certain that this vet probably never entered, much less graduated from vet school, and that he was likely taking pleasure in my suffering,

I begrudgingly took Thor’s reins, swung my dying carcass up on his noble back and headed into “The Darkness.”

If you’ve never ridden this ride, you don’t know what darkness can be. At times you can wave your hand in front of your face and can’t see it. I was greeted every few minutes by waves of increasing nausea and delirium as we wound our way down, down, down to the Francisco’s vet check, a God-forsaken patch of grass that seemed as good a place as any to die.

I offered my horse to the control judge, and I cursed him under my breath as he told me, “Your horse looks good. You better get moving.” And then “those words” came out of my mouth. Words I hate to ever say, that sounded as if someone else was speaking them, that tasted bitter as I said them, that were driven by nausea and fatigue: “I can’t.”

I remember lying down on a lounge chair. Someone threw a sleeping bag over me, and I passed out. I slipped in and out of consciousness for a few hours, and I remember Thor’s soft footsteps as he quietly grazed next to me and never left my side.

Then there was the arduous trailer ride back to Auburn—rough and slow, perfectly punctuating the end of that fateful day. That moment—when I decided I couldn’t go on—haunts me to this day, and likely is a large part of what drives me to accept the challenge of the Tevis trail every year that I can.

I have learned to enjoy the beauty of that trail, and to relish the sometimes harsh lessons it can dish out. There are few adventures left for us to experience in today’s world that challenge us, show us what we’re made of, force us to face our fears, overcome our weaknesses and keep moving on the way that the Tevis does.

Sunburn, the sting of sweat in your eye, the gritty feel of Tevis dust between your teeth and in your nose and ears and socks and eyes and hair and places I can’t mention here. Chafing, aching, fatigue, sleep deprivation—you name it, it’s all there for you.

As Hal Hall, 30-time Tevis finisher, is fond of saying, the Sierras are “unforgiving to the ill-prepared.”

(Incidentally, Thor’s final career record was perfect—except for the day I asked him to quit at Tevis. Dang.)

I made five more attempts, each ending short of the finish line. Some were due to unpreparedness on my part, one lameness, and one very frightening colic that could have easily taken the life of my horse if not for the caliber of vets that work the Tevis each year.

I have watched my wife, whom I introduced to the sport, win a 50th Anniversary buckle while I was still holding my pants up with baling twine.

Then, finally, the Tevis gods had apparently had enough entertainment at my expense, and something magical happened. I had converted to riding gaited horses around 2002, and in 2008 I bought an unlikely looking, unpapered Tennessee Walker named John Henry.

He’s compact and muscley, and not much to look at. I just thought he would be a fun play-thing kind of horse, but I soon saw that this horse had a toughness that came from within—he showed up with it, so to speak.

He cruised easily through his first few 50s, and I decided (well, my wife gave me permission) to see if I could get him ready for Tevis. I groveled so thoroughly that Dr. Michele Roush agreed to coach me, and we set about the job of getting John Henry fit enough to tackle something as brutal as what the Tevis offers up.

John Henry took everything we threw at him, and I swear I could hear him laughing at me down at the barn late at night. Probably while he was getting another tattoo.

Ride day finally arrived in 2009, and John Henry fought his way valiantly to Robinson Flat, but Coach Roush said she didn’t think he looked as good as he should at that point in the ride. With my heart in my throat, almost fully expecting another pull at some point that day, we headed out from Robinson to tackle as much of the trail as we could. I felt we at least had to put in a good effort.

Michele stopped me before I departed, handed me four double-dose syringes of electrolytes, looked at me sternly, and said, “These will be gone by Foresthill!” I remember mumbling, “Yes, ma’am,” as we turned to leave, and I think I sucked my thumb halfway to Dusty Corners.

Well, I did what I was told, and John Henry began to drink like a sailor on shore leave in response to his electrolytes. At Foresthill, Dr. Jim Baldwin examined him and told me, “Let him rest and get some chow, and he’ll take you home. You have a lot of horse here.”

From that point on, John Henry became nearly unstoppable—a runaway freight train. He ate and drank feverishly, pounded through the night and, finally, deposited me at the finish line for my first Tevis completion. Ever. I still have to take a moment whenever I remember it.

Nice story, but what could it mean for those who aspire to wear that elusive Tevis buckle? (Side note: More people have summitted Mt. Everest than wear a Tevis buckle.) I hope it can mean that the longer and tougher the journey, the sweeter the rewards.

It can mean finding something in yourself and your horse that you have felt but have never proven to yourself is there. It can mean that several failures can be the stepping stones to success. Or, it can simply mean a very scenic ride on a good horse for as long as the two of you choose to carry on. All pretty heady stuff, and worth lying awake a few nights to ponder.

With a little luck I hope to ride the Tevis once again. Oh, and John Henry? He has finished three in a row—2013, 2014 and 2015—under the guiding hand of his new owner, Dr. Susan Garlinghouse. Together, they have found things in each other they might not have found otherwise. It’s all good stuff.

Lastly, some words for you Tevis dreamers, and I know you’re out there: Life is so very short. It’s good to get a little dirty every now and then. I double-dog dare ya.

You can follow Bruce and Trooper and all the entrants at this year’s Tevis Cup ride via http://teviscup.org/.

About AERC: The American Endurance Ride Conference (AERC) was founded in 1972 as a national governing body for long distance riding. Over the years it has developed a set of rules and guidelines designed to provide a standardized format and strict veterinary controls. The AERC sanctions more than 700 rides each year throughout North America.

In addition to promoting the sport of endurance riding, the AERC encourages the use, protection, and development of equestrian trails, especially those with historic significance.

Many special events of four to six consecutive days take place over historic trails, such as the Pony Express Trail, the Outlaw Trail, the Chief Joseph Trail, and the Lewis and Clark Trail. The founding ride of endurance riding, the Western States Trail Ride or “Tevis,” covers 100 miles of the famous Western States and Immigrant Trails over the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

These rides promote awareness of the importance of trail preservation for future generations and foster an appreciation of our American heritage.

For more information please visit us at www.aerc.org

Press release provided by Troy Smith, AERC Publications