Equine Protozoal myeloencaphalitis (EPM), also known as "sleeping sickness" can appear in foals only a few days old or horses in their 30s. Any age, sex or breed can develop it, although young horses, and those shipped frequently, seem to be at greater risk.

Sources and links - EPM in horses

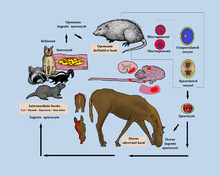

Since its discovery more than 25 years ago, the origin of EPM infection in horses has pointed to opossum feces containing sporocysts, cysts that contain spores able to reproduce asexually.

Since its discovery more than 25 years ago, the origin of EPM infection has pointed to opossum feces containing sporocysts (cysts that contain spores able to reproduce asexually).

When feed, grass, or water are contaminated, and then ingested by a horse, these sporocysts hitch a ride. The cysts erupt and protozoa leave lesions along the spinal cord and brain stem, producing an array of clinical signs that vary from horse to horse.

Early signs can be anything from a slight stumbling or lameness to an odd tilt of the head. Overall lethargy and weakness can sometimes quickly turn to recumbency and death.

If EPM attacks the brain stem, the results are depression, behavioral changes, facial nerve and/or tongue paralysis, roaring, vision problems, drooping eyelids, and difficulty swallowing.

The progression of the disease may take a few hours or can occur over weeks, months or years. Progression may occur steadily or may stop for a period of time, only to begin again.

At least 60% of horses improve with treatment, but less than 25% ever recover completely. Relapses are common in horses that continue to test positive, but rare in those that test negative after treatment.

According to researchers at UC Davis, 30% to 60% of horses in North America have antibodies to the primary protozoal parasite responsible for EPM, S. neurona, making the disease difficult to diagnose: “At present, definitive diagnosis of EPM relies on post-mortem examination of neural tissue. No test in the live horse is currently considered definitive.”

Currently, some equine health practitioners who are versed in Eastern medicine, i.e. acupuncture, Chinese herbs, etc., are turning to the use of holistic medicine, both to diagnose the disease when early warning signs appear, and to treat horses diagnosed with EPM.

Traditional medicine veterinarians are beginning to believe they can learn more about EPM by keeping an open mind to alternative medicine, which can minimize the dependency on drugs, save money, and ultimately and most importantly, save the horse.

According to Dianne Volz who has dedicated more than 20 years to using acupuncture points, electric muscle stimulation, ultra- and infra-sound, and laser and photon therapy to check horses' immune systems, a systematic examination of a horse using acupuncture points can help in diagnosing EPM in a horse and can also lead to better treatment.

In addition, keeping barns and horse areas clean and unattractive to nocturnal opossums is standard protocol to minimize risk of infection.