Researchers at the University of Liverpool in the England addressed the question of whether the time of year/season has an effect on the number of horse colic cases. During the study, a clear fall/winter peak was found for impactions, spring for equine grass sickness (a problem in the United Kingdom likely associated with exposure to the bacterium that causes botulism), and with peaks in both the spring and fall for all other types of horse colic.

Colic - more than a tummy ache

More time spent in a stall, reduction in level of exercise and/or turn out and change of roughage in diet are factors in colic.

Management factors were not specifically analyzed in this study, but the authors did discuss how their findings might tie in with those of other studies that did look at management. These aspects included more time spent in a stall, reduction in level of exercise and/or turn out and change of diets either higher or lower in roughage.

Information from large breeding farms suggests that the routine of feeding horses grain after being brought in from pasture and then keeping them in stalls for part of the day increases the risk of colic, and specifically colon tympany and displacement of the large colon.

By altering this daily routine, including keeping horses turned out after grain feeding, colic incidence is decreased. Similarly when hay is available to horses on lush pasture, the hay will be consumed as part of the diet, and incidence of colic is decreased in horses turned out.

Sudden changes in a horse’s activity level, diet and stabling increase the risk for colic. Horsemen and veterinarians have long observed that horses kept on pasture colic less than those spending most of their time in stalls.

In addition, research from the University of Nottingham in England suggests that changes in intestinal motility may account for that decrease.

In the study, researchers selected 16 horses and divided them into two groups. The first group of eight (Group A) was kept in stalls bedded with shavings for two weeks and turned out each day for 60-90 minutes of free exercise. They had continuous access to fresh water and were fed hay and grain twice a day. The second group of eight (Group B) was kept on grass pasture 24 hours a day, with continuous access to fresh water. They received no grain or forced exercise.

After two weeks, the groups were switched, with Group B being placed in stalls and Group A turned out to pasture for an additional two weeks following a gradual introduction period to their new surroundings and feed.

During the study, each horse’s intestinal motility was measured twice daily using ultrasound to chart the number of gastrointestinal contractions. Keep in mind that intestinal contractions are how the horse moves feed through its intestinal tract to digest it.

Keeping your horse healthy means monitoring his weight in order to avoid common health issues such as equine metabolic syndrome, laminitis and Cushing’s Syndrome.

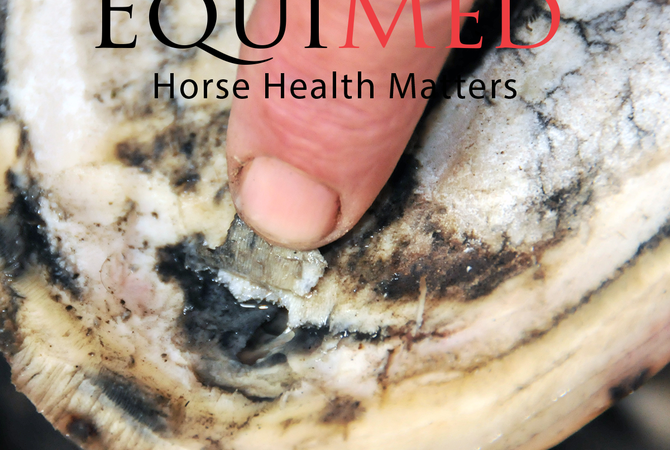

When the study was completed, it was found that intestinal motility was significantly lower in stabled horses than in those kept on pasture. Slower motility means that food is retained longer; therefore, the intestinal contents become drier. This was especially true in the pelvic flexure, where the horse’s colon narrows and turns back on itself. This portion of the intestinal tract is the most common site of colon impaction due to dry intestinal contents, which are a major cause of colic during the winter months when horses are not drinking enough water.

While the study did not determine why there was decreased intestinal motility in stalled horses and a greater probability for impaction colic. Since neither group of the horses in the study was fed a large amount of food or subjected to hard work, it appears that water intake, either through drinking or grazing, as well as regular low-level exercise seems to support normal intestinal motility and a decreased incidence of colic.