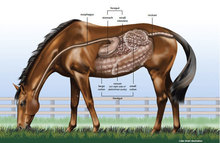

Dr. Lydia Gray addresses the equine gastrointestinal tract and how its complexity relates to colic and other digestive problems in horses in her latest release by SmartPak. As Dr. Gray states, the equine gastrointestinal tract can be divided into two main sections: the foregut and the hindgut. The foregut consists of the stomach and small intestine while the hindgut or large intestine is made up of the cecum and colon.

The horse's digestive system

Colic is simply a general term meaning abdominal pain and by limiting the proven risk factors as much as possible can go a long way toward keeping a horseâs GI tract operating smoothly.

© 2015 by SmartPak

The equine stomach is only able to hold 2-3 gallons at a time, making it the smallest stomach in relation to body size of all our domestic animals. Depending on how big the meal is and what it contains (e.g. hay vs. grain vs. liquid) food may remain in the stomach as little as 15-30 minutes or as long as 12 hours, with 3-4 hours being average.

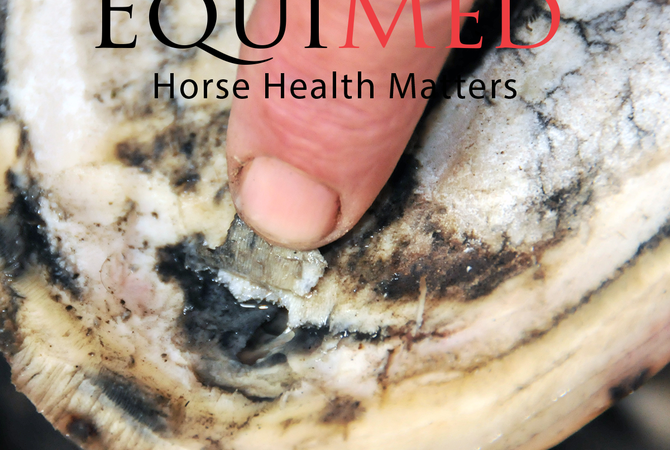

Dubbed the ânon-glandular region,â the upper 1/3 or so of the stomach is where 80% of ulcers form since this area does not have protection from acid like the lower, glandular portion does.

The next part of the tract is the small intestine. Approximately 70 feet in length, it is made up of three parts: the duodenum, jejunum, then ileum. Food moves through the entire small intestine in as little as 30-60 minutes but can take longer, up to 8 hours.

Continuing on to the large intestine, the first layover is the cecum. Basically a fermentation vatâsimilar to the rumen of a cowâthis comma-shaped structure on the right side of the horse is approximately 4 feet long and holds 8 gallons. From the cecum the order is the large colon (10-12 feet long), then the small colon (also 10-12 feet long). Time for passage through the whole hindgut can range from less than 1 day to as many as 3 days.

The Equine Digestive Process

Since the functions carried out in the front of the gastrointestinal tract versus those carried out in the back of the GI tract are very different, it makes sense to focus on each part separately.

Foregut digestion

After food is gathered up, chewed, and swallowed, the stomach kicks into gear. The main functions of the stomach are to add gastric acid to help with the breakdown of food, to secrete the enzyme pepsinogen to begin protein digestion, and to regulate the passage of food into the small intestine. Basically the stomach is a holding and mixing tank, not unlike a cement truck that is constantly churning and mixing ingredients.

While food breakdown may begin in the stomach, it continues in the small intestine, where secretions help with the further digestion of protein, simple carbohydrates, and fat. The small intestine is also the main site of nutrient absorption once they are in small enough form. Amino acids, glucose, vitamins, minerals, and fatty acids are taken into the body as they move along the small intestine, so progress shouldnât be too fast or too slow.

Hindgut digestion

The processes that occur in the cecum and colon are less about breaking down food into smaller, absorbable particles with the aid of enzymes and more about fermenting complex carbohydrates (fiber) into useful end products with the assistance of the âgood bugs.â

In addition to generating fatty acids, which supply energy or calories, these helpful microorganisms also produce B-vitamins, Vitamin K, and some amino acids. The colon then serves not only to absorb these nutrients but also a portion of the water that accompanies food as it moves along the digestive tract.

Horse Digestive Problems

With all these moving parts, itâs no wonder sometimes things donât always run smoothly. However, just because the digestive tract of the horse is long and complicated shouldnât keep owners from doing their part to help maintain a healthy digestive system. To understand where best to focus these efforts, itâs important to understand the most common problems of the foregut (gastric ulcers) and the hindgut (colic).

Gastric ulcers or, erosions in the stomach lining, occur because sensitive tissue undergoes prolonged contact with irritating acids. In the short-term prescription medication may be needed for tissue healing, but in the long-term a combined approach of pharmaceuticals, natural agents, and dietary and management changes may be required to maintain healthy stomach conditions.

In particular, ingredients like sea buckthorn, glutamine, aloe vera, pectin, and lecithin have been shown to be especially helpful in supporting overall stomach health.

âColicâ is simply a general term meaning abdominal pain. Despite the fact that it doesnât point to any specific cause or location in the belly of the horse, limiting the proven risk factors as much as possible can go a long way toward keeping a horseâs GI tract operating smoothly.

Abrupt changes in hay or grain, large amounts of grain, abrupt changes in activity, large amounts of stall time, poor parasite control, and lack of access to water have all been linked to colic. On the other hand, digestive supplements like prebiotics, enzymes, and yeast have all been shown to support normal hindgut activity.

Horses will be horses, and no feeding or management system can fully prevent the accidents and injuries or disorders and conditions they are prone to. But gaining a better appreciation for whatâs normal and not-so-normal when it comes to the elegant yet fragile GI tract of the horse can still make a big difference!

By: Dr. Lydia Gray, DVM, MA SmartPak Staff Veterinarian and Medical Director