In light of the current pandemic, it's helpful to go back a bit and examine how West Nile virus (WNV) came into this country and how it behaved.

Horse drinking from a stagnant pool of water

The natural pattern of a new disease is a high rate of infection because horses (in this case) have no disease resistance, since the immune system does not recognize the new bug.

© 2016 by Peter Gudella

Although the method of transmission is totally different to the current corona virus, we can learn lessons from it.

West Nile virus was unknown in the United States until 1999 when 13 out of 25 reported cases of horses that contracted the virus and died on Long Island, New York. The disease had been in Europe and parts of Africa for many years, but the horses in those countries had natural immunity to pass along to their offspring.

Although the disease was severe when a horse became infected, it did not wipe through the population. In the United States there was no natural immunity, so the death rate was initially extremely high.

The horse community panicked because the death rate was so high. Vaccines were rushed to the market. Nobody had bothered to create one previously for the smaller countries. Vaccine use was even advertised on the radio; a rare event for anything in the equine industry.

The initial natural pattern of a new disease is for a high rate of infection to occur because the animals (or humans) have no disease resistance. In other words, the immune system does not recognize this new bug, so it cannot protect the body. Infected or exposed animals who have a strong immune system, may or may not show mild signs of the disease.

When the immune system has been exercised by exposure it produces antibodies (special immune cells) against the disease, ready and waiting to protect against any exposure. Animals who get sick and recover usually also have these antibodies.

Once the immune system has been activated, the animal is able to pass along immunity to its offspring. New offspring and older horses with antibodies begin to form a group of naturally resistant horses. The numbers of active cases went down. With West Nile virus, both the human and equine cases followed this pattern.

The equine WNV disease spread to 65 cases in the second year, with most still in the Northeast. By 2002, there were over 14,000 cases across most states. But, in 2003 that number dropped to just over 4,400 cases, and in 2009 there were just 241 cases across the country with many states reporting only a few.

There are about 9.2 million horses in the country, so you can see the infection rate and therefore the risk of the disease is extremely low. There are a few hotbeds of activity, but these are widely scattered.

Vaccination takes the credit for the reduction in numbers of equine cases. No humans have been vaccinated and yet there is approximately the same pattern of disease increasing, then decreasing, with only a few human cases currently reported each year.

Vaccination in the horse population is not 100 percent by any means, since many horses across the country are not vaccinated regularly. Horses from low income areas are often not vaccinated because of the expense.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website (https://www.cdc.gov/westnile/index.html):

“There are no vaccines to prevent or medications to treat WNV in people. Fortunately, most people infected with WNV do not feel sick. About 1 in 5 people who are infected develop a fever and other symptoms. About 1 out of 150 infected people develop a serious, sometimes fatal, illness.”

So, WNV is still a serious disease in people, yet we hear little about it because it's not common. Check on the actual human incidence in your area on this page (scroll down to see the maps): https://www.cdc.gov/westnile/statsmaps/cumMapsData.html#seven. Most parts of the country have no cases, but there are some places the disease is more common.

There does not seem to be reporting for just equine cases, but if you are in an area with many human cases, check with your veterinarian to see the incidence in your specific area.

So, what is West Nile virus disease?

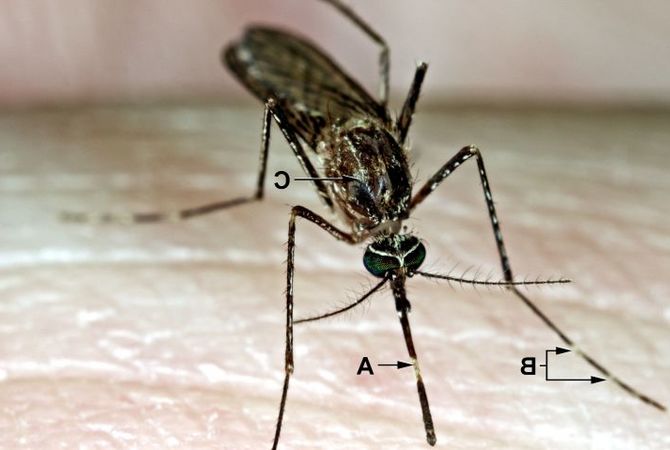

It is a viral disease, primarily caused by the northern house mosquito that bit a bird infected with WNV, then bit a horse or human. Your horse cannot catch WNV from another horse, it must go through the birds. Crows and blue jays are the most common killed by it. If these birds are dead on your property, contact the local authorities for a test.

The symptoms can be variable but usually involve some loss of coordination, impaired vision, muscle twitching, fever, inability to swallow, circling, hyperexcitability and other bizarre behaviors. The signs can mimic other neurologic diseases including rabies, botulism, EPM (equine protozoal myelitis), herpes, and eastern, western or Venezuelan encephalitis.

Call your vet immediately if your horse is behaving oddly, since any of these diseases can be life-threatening and rabies can be transmitted to humans easily. A blood test is needed to confirm the diagnosis.

The conventional treatments for WNV are only to support the horse while it works though the disease with its immune system. There are no antiviral drugs that are effective or even available. Fluids, anti-inflammatories, and protection from injuring themselves while uncoordinated are the main treatments.

Natural treatments are extremely useful, especially homeopathic remedies. Supplements and herbs for the immune system are helpful, particularly vitamin C, echinacea, Isatis herb, and astragalus. Homeopathic medicines should be used with an experienced veterinary homeopath as the disease can be serious and the remedy needed can change rapidly.

Homeopathic remedies to consider include belladonna (and this may be one of the most important, but not the only one), aconite, Natrum muriaticum, China (Cinchona), nux vomica, phosphorus, and sulphur. Mild to moderate cases treated with homeopathy and supportive care have recovered well with the use of homeopathy. Severe cases are difficult to treat with any medicine, especially if the horse is down and cannot get up.

Prevention

Standing water is the breeding ground for mosquito larvae. One of the best ways to prevent WNV is to remove any sources of standing water around the farm, including cleaning gutters, removing old buckets or cans or discarded tires.

Mosquito dunks containing a harmless bacteria (Bt-israelensis) can be used in water tanks, as can goldfish if you have large tanks. Stagnant water breeds mosquitoes after just four days.

Vaccination is considered the key to prevention of WNV. Go back to the beginning of the article and think about whether vaccination is really needed. Check the CDC website for the number of cases in your state or county. Many states have zero to three cases and hundreds of thousands of horses, so the incidence is extremely low.

The American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) has issued a guideline about vaccines and considers WNV one that every horse should have. My practice has been testing the antibody titers (the measure of the immune response to vaccines or disease).

The majority of horses have a very strong titer, even some who were not known to be vaccinated or sick. This indicates there may have been some natural exposure.

The vaccines have many reports of side effects; however, it has been hard to prove that to the satisfaction of the drug companies. To vaccinate or not is a personal decision: consider the risk of contracting the disease (with WNV – low depending on your area), the risk of the disease itself (moderate to serious disease), and the risk of the vaccine (reports of side effects are plentiful).

Then make your own decision based on your situation and occurrence of the disease in the horses in your area. Ask your veterinarian how many cases she/he has seen in the last one to two years.

From a holistic perspective, vaccinations have been documented to stress the immune system, especially when multiple vaccines are given repeatedly twice yearly. Many horses’ immune systems become compromised, with allergies, illness, and poor performance as the main sign.

When treated with homeopathy and Chinese medicine for vaccine-related signs, the horse’s health improves dramatically. The more immune compromised an animal is, the more likely they are to come down with every disease, including WNV.

The best way to improve your horse’s immune system is to feed whole foods, whole food supplements when possible, along with general immune supplements such as flax or chia seeds, and herbs. If your horse has signs of any chronic problem, including “just” poor quality coat, poor feet, a bit of a cough or something like that, find a holistic-minded veterinarian to help guide you towards better health for your horse.

References

Mosquito Dunks: www.planetnatural.com/site/mosquito-dunks.html

Whole Foods Diet: https://holistichorse.com/health-care/demystifying-the-whole-foods-diet/

Dr. Joyce Harman owns Harmany Equine Clinic, Ltd., a holistic veterinary practice in Washington, Virginia. Visit www.harmanyequine.com.

Article by Joyce Harman, DVM, MRCVS

Press release provided by Sheila Whaley