As the summer intensifies and the temperatures rise, we are reminded of the impending threat posed by West Nile virus (WNV).

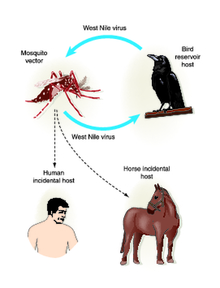

Diagram showing pathway West Nile virus takes from bird to mosquito to horse or human.

Summer and early fall seasons witness a surge in mosquito populations due to the heat, humidity and rain, making it a crucial period to use preventative measures against the West Nile virus.

© 2020 by Department of Health

WNV is primarily transmitted through mosquitos as a vector and that it is a viral infection that affects birds and mammals, including horses and humans. Summer and early fall seasons witness a surge in mosquito populations (due to the heat, humidity and rain), making it a crucial period to use preventative measures against the disease.

The virus can manifest in horses with varying degrees of severity, from mild symptoms like fever, depression, weakness, muscle tremors and loss of appetite to more concerning neurological signs such as ataxia, head-pressing, difficulty swallowing and seizures. In severe cases, the infection may be fatal. WNV isn’t to be taken lightly. According to the American Association of Equine Practitioners, this virus has been shown to be fatal in 33% of horses that exhibit clinical signs of disease.1

Symptoms

• Stumbling

• Lack of coordination

• Muscle twitching

• Weak limbs

• Depression

• Loss of appetite

• Head pressing

• Facial paralysis

• Aimless wandering

• Convulsions

• Coma

West Nile virus is transmitted from birds, often referred to as avian reservoir hosts, by mosquitoes, and infrequently by other bloodsucking insects, to horses, humans and a number of other mammals. Horses and humans are considered to be dead-end hosts for West Nile Virus because the virus is not directly contagious from horse to horse or horse to human, and indirect transmission via mosquitoes from infected horses is highly unlikely as these horses do not circulate a significant amount of virus in their blood.

Vaccination against the West Nile virus is the best method of prevention. A USDA licensed vaccine is recommended as a core vaccine and is an essential standard of care for all horses in North America. Four USDA licensed vaccines are currently available (two are inactivated whole WN virus vaccines; one is a non-replicating live canary pox recombinant vector vaccine and one is an inactivated flavivirus chimera vaccine):

All of the current WN vaccine products carry one year duration of immunity, with challenge, consistent with their respective label claims.

In addition to a sound vaccination protocol recommended by a veterinarian, simple insect control measures should be utilized and insect repellents used when horses are in areas exposed to mosquitoes. Horses should be stabled during dusk and dawn hours and other times when mosquitoes are present and good use of fan to insure insects don't invade barn and stable areas is important.

In addition, horse owners should eliminate opportunities for mosquito breeding by draining wet areas of pasture, filling puddles, repairing eve troughs, gutters, and clearing any containers that might hold even small pools of water.

Draining water tanks once or twice weekly should be a priority during mosquito season. Additionally, controlling mosquitoes in ponds and large water containers through the use of larvacides and fish helps keep the mosquito population down.

Treatment is vital for any horse with WNV. At the present time there is no specific "medicine" for a horse that develops WNV, although there are some promising advances being made in that area. Working with a veterinarian who is able to provide supportive therapy can save the horse’s life. For advanced cases, horses usually have to be hospitalized. For mild cases, home care may be adequate. Proper nursing care and treatment is important to the recovery process and each animal is assessed according to it's age and health.

Over the last few years, it has been discovered that of those horses that recover, some will relapse within a few months or a year and some will die.

The main focus of veterinarian aided therapy is to decrease brain inflammation, treat the fever, if any, and provide supportive care, which may require 1-4 weeks of intermittent therapy.

Common medications recommended by veterinarians include flunixin meglumine (Banamine), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and dexamethasone. Sometimes fluid therapy is needed for animals that are not able to drink to prevent dehydration.