Another case of Hendra virus was detected last week in Queensland, Australia. News agencies reported that a veterinarian treated a gravely ill horse in the northern part of the state. Lab results confirmed that the animal had Hendra virus (HeV), a severe virus of the Henipavirus genus that can cause fatal neurological and respiratory disease in horses and humans.

Flying foxes carriers of horse disease

Lab results confirmed that the horse had Hendra virus of the Henipavirus genus that can cause fatal neurological and respiratory disease in horses and humans.

Upon confirmation of infection, the horse was humanely euthanized.One person was exposed to the virus, but officials say that the risk of infection was low, as he had worn full protective equipment. With a case fatality rate of over 50 percent in humans, and no effective antiviral therapy, prevention of infection through appropriate control measures remains essential.

HeV was first recognized in the mid-90s in the Queensland suburb of Hendra following a spate of respiratory disease in 21 horses. It is thought that the virus is indirectly transmitted to horses through ingestion of flying fox excreta, partially eaten fruit, or feed contaminated with reproductive fluids from bats commonly known as fruit bats or flying foxes (bats of the family Pteropodidae, specifically the spectacled, red, and grey-headed flying foxes) – the natural hosts for HeV.

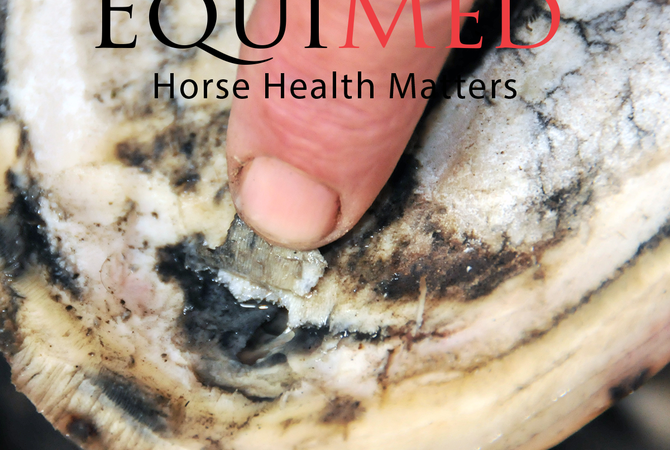

While there is no apparent disease in infected bats, symptoms in humans include fever, muscle pain, headache, vertigo, and enlarged lymph nodes. Horses infected with HeV may display symptoms such as increased body temperature and heart rate, respiratory distress, nasal discharge, “wobbly gait”, anorexia, and muscle twitching. The incubation period in horses is between 5 to 16 days with a case fatality rate of approximately 75 percent.

Though human infections are rare, HeV can be passed on to humans if they come into close contact with bodily fluids from an infected horse. As of October 2011, seven human cases of infection have been confirmed resulting in four deaths. All infections in humans have occurred as a result of exposure to body fluids of HeV infected horses. No human-to-human transmission has ever been recorded.

Currently, a vaccine for horses is undergoing final clinical trials. However, there are no vaccines or antiviral therapies available for treatment of HeV infection in humans.

The Queensland property where the horse was kept has been quarantined, and an investigation is underway to inspect neighboring areas. "We're quite happy we've got this disease contained on the property so it's not going to spread to other properties in the area, nor is it a risk to the racing industry or other horse events in the area,” said Rick Symons, Queensland’s chief veterinary officer.

This is the state’s fourth HeV-related incident so far this year, according to Symons, following one outbreak that occurred in January and two others in May.

The Disease Daily reported on outbreaks last year that occurred in New South Wales and in Queensland where eight people were exposed to the virus. Ecological factors such as deforestation, hunting, loss of habitat, and commercial logging appear to be some of the environmental factors that have contributed to changing flying fox population dynamics and the increased number of HeV events.