The number of horses in the United States confirmed with the parasitic infection equine piroplasmosis, as a result of an outbreak in Texas, now stands at 409.

The US Department of Agriculture's latest report to the World Organization for Animal Health [Dated October 4-8, 2010] said more than 2,300 horses have been tested for the disease as part of its ongoing investigation into the outbreak, first detected on a property in Kleberg County, Texas.

To date, 409 horses have tested positive to the disease, one more than in the previous report filed August 25.

Dr. John Clifford, deputy administrator with the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, said all cases had been directly linked with the Kleberg County index premises. Horses who have tested positive are in Texas, Alabama, Louisiana, Indiana, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

The positive horses either currently live or previously lived on the index premises, live next door, or are dangerous contacts such as a positive foal born to an infected mare, or temporarily boarded on index premises or are from high-risk premises (located near the index ranch and have similar terrain and tick populations).

In an unrelated outbreak involving two cases in Minnesota and two in Louisiana, the agriculture department has formally declared it resolved.

The source of the outbreak was listed as unknown or inconclusive, but the department suggested shared needles or substances between horses might have been responsible for its spread, rather than ticks. [But a source still had to be present. Some horse had to have had the disease for it to pass via shared needles. And this disease passes well by insect vectors but not by needles. The dose in a needle is not nearly as concentrated as in the insect vector hind gut. So there still had to be a source.]

The outbreak was first reported around Christmas last year. The parasites responsible for equine piroplasmosis are _Babesia caballi_ and _Theileria equi_, the latter being responsible for this outbreak.

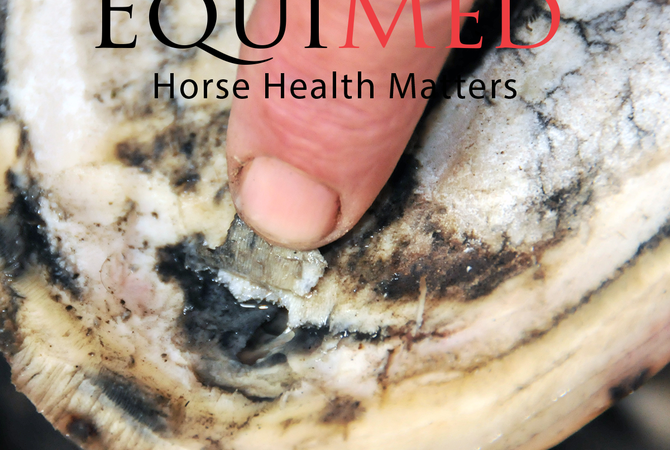

Ticks ingest blood from infected equines and then bite uninfected equines, spreading the disease through the blood-feeding process. Ticks carrying the parasites can be moved from one place to another via hay, bedding, feed and animal to animal.

The disease may also be passed from pregnant mares to foals in the uterus and by contaminated needles and other skin-penetrating instruments. Horses which contract the disease in the United States are usually euthanized to eliminate the risk of spread.

Signs may become apparent 7 to 22 days after infection. Clinical signs include weakness, loss of appetite, fever, anemia, jaundiced mucous membranes, swollen abdomen and labored breathing. Horses that survive the acute infection phase may carry the parasites for an undetermined period of time in their bloodstreams