Premature delivery is a devastating problem in horses since the majority of foals that are delivered before the last week of gestation die. The negative financial and emotional impact of premature delivery on horse breeders is, therefore, substantial. In addition, premature foals rarely have productive performance careers.

Full gestation = Healthy foal

The single most important cause of premature delivery is placental infection, accounting for nearly one-third of all premature births, stillborn deliveries and foal deaths within the first day of life.

© 2012 by April Raine

Researchers at the University of Florida have determined that the single most important cause of premature delivery is placental infection, accounting for nearly one-third of all premature births, stillborn deliveries and foal deaths within the first day of life. In spite of the magnitude of this problem, little progress has been made in understanding how placental infections can be prevented or treated in an economic, practical way.

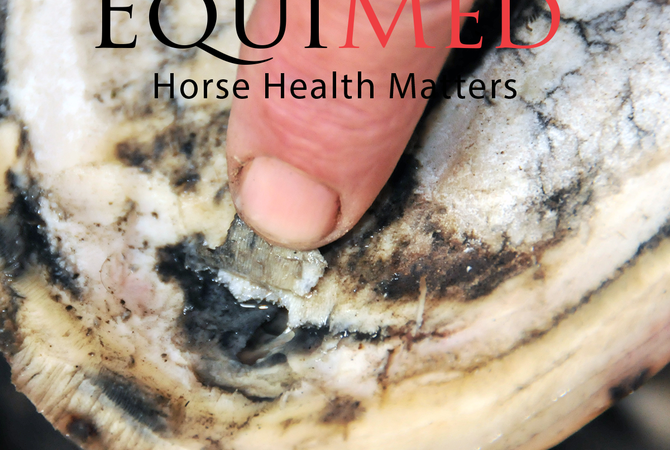

The placenta is a critical organ that needs to be examined in all abortion and premature delivery cases. It should always be examined thoroughly by the attending veterinarian and should be submitted to a diagnostic laboratory for histopathological evaluation whenever a foal is born early.

Owners should also save the placenta from every normal term delivery for veterinary examination, as the placenta was the foal’s “house” for 11 months. If there are any irregularities within the placenta, it many times results in poor health of the foal during the first weeks of life.

The majority of infections are caused by bacteria ascending through the vagina and entering the uterus through the cervix. As more and more of the placenta becomes irritated, it begins to pull away from the uterine lining.

This results in the fetus receiving less oxygen and thereby retarding its growth and adversely affecting its ability to survive. Affected mares can frequently be identified as they will have a vaginal discharge and filling of the udder with milk, which will stream down their legs.

Unlike in women, when the birth of a baby can be induced, the practice of causing the early delivery of a foal by injecting oxytocin if the mare is experiencing problems is not recommended. The horse fetus is quite unlike other species in that it only matures in the final five to seven days of pregnancy and if removed from its mother before then, it frequently will die.

Unfortunately, predicting when a normal mare will foal is difficult because gestation length varies tremendously, ranging between 320 to 360 days. A unique response of the equine fetus to placental infections is that a viable foal matures more quickly due to the stress and can be born before 320 days of gestation, if the infection develops slowly and premature delivery can be delayed.

Therefore, if infected mares could be identified early, and treated so that delivery could be delayed, more foals might survive.

Researchers from the University of Florida developed a model of ascending placental infection so that many aspects of the disease could be monitored. They found the severity of the placental infection could be identified by measuring hormones in the mare’s blood and by evaluating changes to the placenta that was near the cervix through ultrasonography.

In addition, as the placental infection progressed, inflammatory substances in the fetal fluids increase the tension of the uterine wall about 48 hours before the mare aborted her foal. The increased uterine wall tension led to decreased oxytocin supply to the fetus and ultimately its death.

An unfortunate finding was that about one fourth of the mares did not develop either a vaginal discharge or milk in their udders. These findings indicate that placentitis may be “silent” disease.

The model of infection is now being used at several institutions to determine how to best treat ascending placental infections. Important breakthroughs have occurred recently, such as the demonstration that treatment of infected mares with antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs and progestins results in the birth of viable foals.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to near impossible to determine when an infection begins in clinical practice, so it is imperative that better diagnostics be developed. Many of the studies are collaborative efforts between institutional groups. Collaboration greatly increases the resources and opportunity for continued major breakthroughs that could reduce the incidence of fetal death.

Much research remains to be completed, including determining how placentitis develops in the mare, development of accurate methods for early diagnosis and determining the best drug combination for treatment.