At a minimum, 320,000 viruses exist among mammals, according to a new study. Identifying these infectious organisms could help alleviate disease outbreaks through early detection -- but compiling evidence on these viruses would cost up to $6.3 billion, researchers say.

Flying foxes - bats - Key to virus research

Although 70 percent of new viral diseases, such as HIV/AIDS, West Nile and SARS, are infections that cross from animals into humans known as zoonoses, researchers say their estimate is first to project the number of viruses among any wildlife species.

"For decades, we've faced the threat of future pandemics without knowing how many viruses are lurking in the environment, in wildlife, waiting to emerge. Finally we have a breakthrough -- there aren't millions of unknown virus, just a few hundred thousand, and given the technology we have it's possible that in my lifetime, we'll know the identity of every unknown virus on the planet," study corresponding author, Peter Daszak, president of EcoHealth Alliance, said in the news release.

Although 70 percent of new viral diseases, such as HIV/AIDS, West Nile and SARS, are infections that cross from animals into humans known as zoonoses, the researchers say their estimate is the first to project the number of viruses among any wildlife species.

However, this hefty price tag is just a small fraction of the economic toll that is caused by major pandemics, like SARS, according to researchers at the Center for Infection and Immunity (CII) at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health.

Prevention of viral outbreaks is critical because antiviral medications are often difficult to develop, the authors pointed out in a school news release.

"Historically, our whole approach to discovery has been altogether too random," lead study author Simon Anthony, a CII scientist, said in the news release. "What we currently know about viruses is very much biased towards those that have already spilled over into humans or animals and emerged as diseases. But the pool of all viruses in wildlife, including many potential threats to humans, is actually much deeper."

For the study, published Sept. 3 in the journal mBio, a multidisciplinary team of researchers examined the flying fox, a type of bat that lives in the jungles of Bangladesh. Flying foxes, the largest flying mammal with a wingspan of up to six feet, are the source of several outbreaks of Nipah virus.

Researchers collected nearly 1,900 biological samples from the bats before releasing them back into the wild, and identified 55 viruses in nine viral families. Only five viruses were previously known. Among the new discoveries were 10 related to Nipah virus.

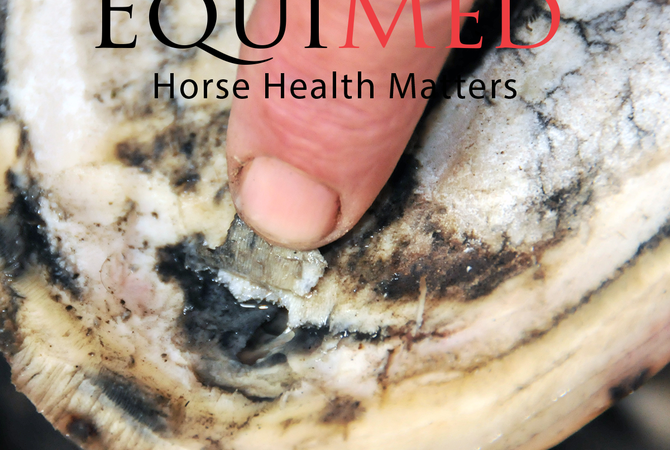

Hendra virus (formerly called equine morbillivirus) is a member of the family Paramyxoviridae. The virus was first isolated in 1994 from specimens obtained during an outbreak of respiratory and neurologic disease in horses and humans in Hendra, a suburb of Brisbane, Australia.

Nipah virus, also a member of the family Paramyxoviridae, is related but not identical to Hendra virus. Nipah virus was initially isolated in 1999 upon examining samples from an outbreak of encephalitis and respiratory illness among adult men in Malaysia and Singapore..

The natural reservoir for Hendra virus is thought to be flying foxes (bats of the genus Pteropus) found in Australia. The natural reservoir for Nipah virus is still under investigation, but preliminary data suggest that bats of the genus Pteropus are also the reservoirs for Nipah virus in Malaysia.

The study authors also estimated that there were another three rare viruses, which were unaccounted for in the samples collected. After increasing the total estimate of viruses in the flying fox to 58, the researchers extrapolated their data to include all 5,486 known mammals. They calculated that there are at least 320,000 viruses.

Senior study author, Dr. W. Ian Lipkin, director of CII, added: "Our goal is to provide the viral intelligence needed for the global public health community to anticipate and respond to the continuous challenge of emerging infectious diseases."