A study by Australian and British researchers based on a population of horses owned by members of Equestrian Queensland who lived within a deï¬ned area in the southeast of the Australian state has revealed the prevalence of equine Cushing's syndrome in older animals and has concluded that many animals with the disease are never properly diagnosed.

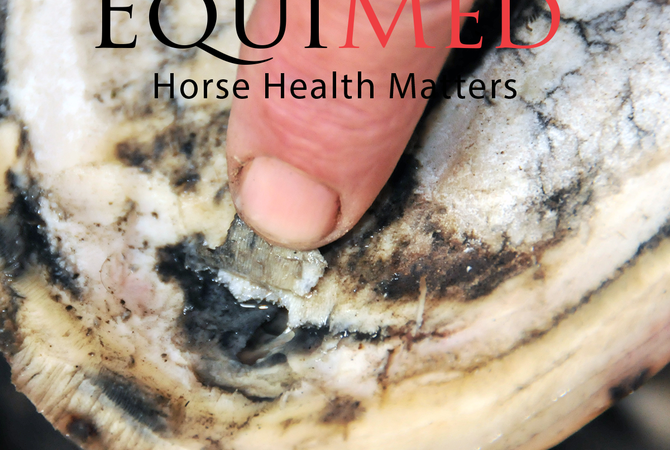

Hairiness - Indicator of Cushing's disease in horses

Study reveals the prevalence of equine Cushing's syndrome in older animals and conclude that many horses are never properly diagnosed.

The study also revealed that excessive hairiness remained the one consistent finding in the diagnosis of Cushing’s in horses.

The study was the first epidemiological study of Cushing’s disease, also known as pars pituitary intermedia dysfunction (PPID), in aged horses in a population unbiased by presentation to, or records obtained from, veterinary practices.

The researchers’ aim was to establish the prevalence, risk factors and predictive clinical signs for PPID in a group of aged horses using seasonally adjusted basal plasma adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) concentrations for confirmation of diagnosis.

The results of the study have been published in the Equine Veterinary Journal.

Owner-reported information was based on an initial postal questionnaire, and all aged horses were subsequently examined. They had samples taken for hematology, blood biochemistry, ACTH and alpha melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH).

In all, 536 owners returned a total of 974 complete questionnaires on aged horses which qualified for the study by being 15 years of age or older.

The researchers said although the sample was not representative of the entire population of horse owners, it would represent the spectrum of PPID among aged horses more closely, rather than those with clear clinical evidence of advanced disease, as has been the focus of veterinary hospital or research herd-based studies.

The prevalence of PPID, based on individual veterinary checks on each animal, was found to be 21.2 per cent in the aged horses, despite owners infrequently reporting it as a known or diagnosed disease or disorder. In this group of aged horses, owners had reported PPID in only 1.6 per cent of the horses – 16 of 974 animals.

The findings highlighted the prevalence of Cushing’s in aged horses and its under-recognition by owners, the researchers from the University of Queensland and the University of Liverpool, said.

Previous studies have looked at owner-reported hirsutism (excessive hairiness) as a means of diagnosis. In this study, owner-reported hirsutism was 16.7 per cent.

“Despite analysis of numerous clinical and historical signs, and biochemical and hematological variables, the only finding found to be consistent with a diagnosis of PPID was owner-reported hirsutism,” the researchers found.

Researchers also found an increasing incidence of PPID with every year of age over 15 years, and the high prevalence of this condition in aged horses and increasing risk with advancing age were consistent with a degenerative condition.

They concluded that aged horses with consistent clinical and historical signs, especially those with owner-reported excessive hairiness, should be candidates for further investigation of possible PPID.

The researchers said it had been suggested that many horse owners may defer seeking veterinary advice for their horses unless the condition is “serious”.

“Many of the signs of PPID are non-speciï¬c, such as weight loss and depression. Others, including muscle wasting, pot belly and hirsutism, have erroneously been considered normal signs of aging in horses.

“Therefore, owners recognizing these signs may not regard them as important enough to seek veterinary advice.”