Horses, being the big active animals that they are often suffer wounds, especially on limbs. Sometimes the wounds are small lacerations. Othertimes, they can be quite severe and take a long time to heal.

Understanding how equine wounds heal

Wound healing in horses has three phases: Acute inflammatory phase, cellular proliferation phase, and the remodeling phase.

When a horse sustains a wound or laceration there are four questions that should be quickly answered as treatment begins:

- Is bleeding easily controlled?

- Will the wound or laceration require stitches?

- Is the wound near a joint, tendon sheath, or bursa?

- Is it a puncture wound?

If the wound or laceration is bleeding, a pressure bandage should be applied immediately and a determination made as to whether or not the bleeding requires a veterinarian's attention.

If an artery has been cut, bright red blood that spurts with the heart-beat may be present. Such bleeding may not stop under pressure alone, so a call to the veterinarian is in order. A veterinarian will be able to stop the bleeding and prescribe treatment to best heal the wound.

Wound healing has three phases: Acute inflammatory phase, cellular proliferation phase, and the remodeling phase. An experienced veterinarian can prevent infection and treat the wound in such a ways that these three phases take place without further repercussions to the injured site.

The first is the acute inflammatory phase, which will help clear foreign materials from the wound. During this phase, a vascular response results in coagulated blood and aggregated platelets forming a clot. Some of these platelets will release chemo-attractants to illicit a cellular response. White blood cells are attracted to the wound to fight infection, remove damaged tissue and start new tissue formation through angiogenesis, the development of new blood vessels, and fibroplasia, the development of connective tissue to fill in the wound.

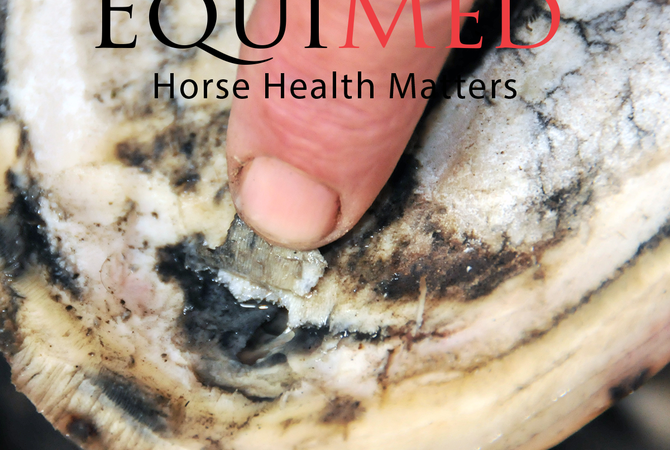

It is important to note here that when the inflammatory phase gets out of control, healing can be compromised later because of development of exuberant granulation tissue - an out-growth of fibrous tissue and blood vessels that commonly occurs in lower leg wounds of horses, often referred to as "Proud Flesh".

This is why maintaining control of the inflammatory process is important at this stage. It is also important to provide a barrier to help prevent additional bacteria from entering the wound as this will elicit additional inflammatory responses.

The second phase is the cellular proliferation phase that begins 3-5 days after the injury. Macrophages debride the wound and produce cytokines that stimulate fibroplasia, the development of fibrous connective tissue, with individual cells called fibroblasts. The fibroblasts then proliferate a new extracellular coating which is rich in fibronectin and hyaluronan.

New capillaries begin to invade the fibrous granulation tissue causing it to appear bright red. In these wounds that are left open to heal, it is necessary for this granulation process to occur. This is what is called second intention healing and this occurs when the wound edges are so far apart they can not be brought together with sutures.

With this granulation bed in place, the epithelial cells can migrate inward to restore the epidermis. It is at this point that the presence of a product which can facilitate cell migration is very important.

The last phase of healing is the remodeling phase. If the previous phases have progressed, this phase will close the wound with very minimal scarring. This is done through the action of myofibroblasts which interact with the ECM, cytokines and growth factors, to apply tension on the existing skin surrounding the wound edges to initiate wound contracture. The final phase is the conversion of the remaining granulation tissue to scar tissue.

The prevention or clearing of an infection is the major key in not prolonging the inflammatory phase of healing, thereby resulting in further inflammation and granulation tissue formation.