Six years after the death of Barbaro from complications related to Laminitis, the veterinary profession is finding new ways to treat the disease, thanks to research and improvements in areas from digital radiography to glue-on horseshoes to cryotherapy, also known as cold therapy.

Barbaro after winning Kentucky Derby

Research and improvements in methods of treating laminitis with everything from digital radiography to cold therapy are helping horses beat the disease.

Promising research is taking place at the New Bolton Center, which has treated horses whose highly publicized bouts with the painful hoof disease in recent years have had very different outcomes: Barbaro, who was euthanized after developing laminitis secondary to his breakdown, and Haskell winner Paynter, who recovered from colitis-related laminitis last year and is back in training.

âWe understand the disease much better now than we did even five or 10 years ago,â said Dr. James Orsini, director of Pennâs Laminitis Institute. âA âshock organâ is an organ that fails related to some sort of systemic disease. In people, the lung is one of those organs. What weâre finding is that the lamellar tissue in the horseâs foot is a similar target organ for the horse."

So, we know that if we can treat these other diseases more effectively â like colitis, or a mare with a retained placenta, or a horse with pleural pneumonia â we can better protect the foot from becoming the shock organ that ultimately fails and results in a crippling disease.

âIf I could identify one or two game-changers,â Orsini added, âIâd say one is our ability to look at the molecular level of the tissue, to actually look at the cells and better understand whatâs occurring on a molecular level relative to the tissue inflammation and the derangement of the tissue. The other thing thatâs helped is we now understand that a technique thatâs been around for hundreds of years â using cold therapy â is one of the best techniques available to us. We can identify the at-risk horse better, and our goal is to prevent the disease rather than have to treat it.â

Veterinarians donât just look to the foot when tackling laminitis. They carefully consider the underlying cause and then try to stabilize that cause, Orsini said. And today, they are applying therapies aggressively to at-risk horses, not just to those showing acute signs of laminitis, said Dr. Bryan Fraley, a farrier and veterinarian whose Fraley Equine Podiatry is affiliated with Hagyard Equine Medical Institute in Kentucky.

Fraley was one of the vets who treated Paynter. That colt underwent cryotherapy well before he showed any distress from the disease.

âItâs been proven that if we ice these horses before they ever show clinical signs, and sometimes even in the early acute stages that are initially painful, we can actually help minimize the changes,â Fraley said. âWe can try to prevent those horses from going from acute to chronic.â

Paynter did develop early signs of the disease, Fraley said, prompting the team to apply casts to prevent his coffin bone from sinking if the laminitis progressed.

âIn my experience, if we apply foot casts with impression material like dental impression material to the bottom of the foot, we give those horses very good support to the center of the bony column,â Fraley said. âWe try to unload the wall and the laminae. In Paynterâs case, it worked.

âIn the past, we were often waiting for horses to show clinical signs,â Fraley said. âNow, weâre trying to identify horses that are at risk before they ever show the first symptom.â

Dr. Hannah Galantino-Homer at Pennâs Laminitis Institute hopes her research into âserum biomarkersâ â molecular changes in the blood that can signal laminitis-induced tissue changes â someday will help clinicians identify signs of laminitis even faster.

âOur overall goal is to find diagnostic markers, like serum tests, that would allow us to detect [laminitis signs] early and to give us some sense of how theyâre going to do â a prognosis,â Galantino-Homer said. âOne marker weâre looking at, we have a horse who was euthanized for supporting-limb laminitis with complete detachment of the hoof capsule, and it looks like that marker went up pretty early. So, if we have a large-enough study with a lot of horses, collecting from the clinic and following through to see what happens, we might be able to correlate that marker with how much damage they have.

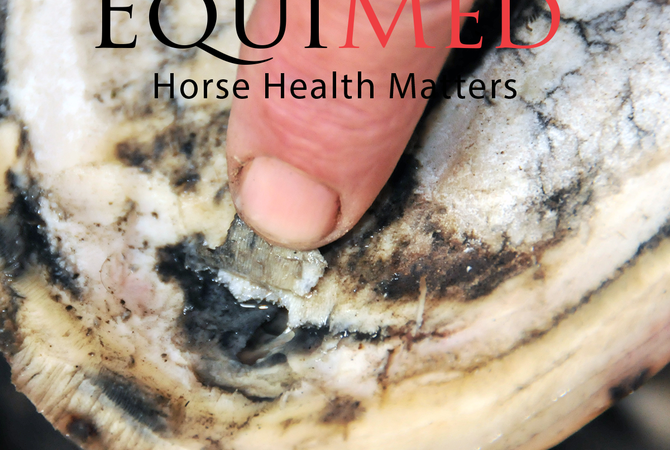

âBecause that damage doesnât always show up until much later,â she added. âPeople talk about taking X-rays and looking at whether the coffin bone has moved relative to the hoof capsule. But that happens after the damage occurs. If we can detect the damage earlier, that would be helpful in those intensively managed hospital cases.â

Another key is to prevent or quickly resolve the issues that lead to laminitis, including catastrophic breakdowns. As in Barbaroâs case, a horse who undergoes surgery to repair one leg is at risk of developing support-limb laminitis, caused by overloading a sound limb as the horse shifts weight from an injured one.

âItâs important to think about any pre-existing bone disease, too, and to ask if we can make bone heal faster,â said Dr. Kurt Hankenson, who holds the Dean W. Richardson Chair for Equine Disease Research at Penn.

Among the practical laminitis-prevention developments to help the post-surgical horse, according to Hankenson: âMats in stalls, which are being used with greater frequency to provide some cushion.â

Hankenson noted that improvements in shoeing technologies, such as glue-on shoes, can aid support for injured horses and potentially reduce the laminitis risk.

Researchers note that the overall funding for laminitis study remains relatively small. More funding would enhance research, but in the meantime, the small community of laminitis researchers has come up with some useful collaborations, Orsini and Galantino-Homer said.

âWe have a lot better technologies in terms of the types of glue-ons and shoes that are out there,â Fraley said. âWe have options, from new polyurethane shoes to better support materials. I think farriers are critically important in the treatment of a laminitic horse. Farriers are usually first on the scene and first to recognize the problem. They often recognize subtle changes, and in acute cases, they can get shoes off quickly, with minimal trauma, and help veterinarians get that horse better foot support.â

Improvements in equine medications for specific conditions that can lead to laminitis, such as Cushingâs disease are being developed, and there is ongoing research into the safest and most effective pain medications.

âThe older nonsteroidals like ibuprofen that we take as two-legged patients, there are now drugs that are very specifically formulated for the horse that are even better anti-inflammatories with fewer side effects,â Orsini said.

More research at the molecular level should mean that more knowledge and better treatments â possibly including stem-cell therapy â are on the way, clinicians and research vets said.