Equine microbiota is defined as the population of bacteria, viruses, fungi and protozoa that are present in or on the horse. The largest number are found in the small and large intestines, but they exist elsewhere too, for example, the nasal passages, the lungs and the skin

Horses eating from a feeder in their pasture

Equines are unable to produce the chemicals and enzymes needed to break down fibrous plant cells and have formed a partnership with microscopic inhabitants of their gut for digestive purposes.

© 2020 by Sedin New window.

Although different from the microbiota that live in human guts, which top 10 trillion; around 10 times greater than the number of cells that form human bodies, equine microbiota may be more numerous and complex than those in the human system..

Although headway has been made in understanding the impact of this microbial world on human health and disease, progress in farm animals and pets is more limited. This may be a reflection of research funding, but also perhaps due to the greater complexity of the intestinal environment especially in herbivores, such as cattle, sheep and horses.

All horses and ponies are at risk of suffering from painful gut-associated conditions. The causes of these can be due to a number of reasons. The dependence on the microbes, the small core population and changes in the diet with resultant shifts in these microbes is often a large factor. Importantly, it is a cause that can be prevented through greater understanding and better management of the horses in our care.

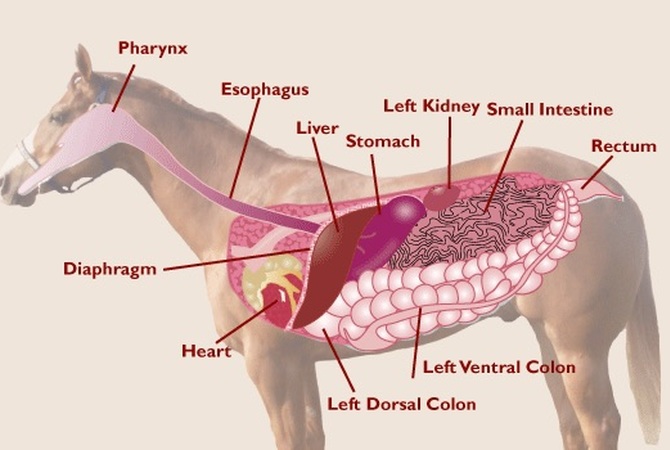

The equine gut is very different than the human digestive tract

Horses eat different types of plant material. To maximize the access to the nutrients contained within, they are dependent on their microbial population. Alone, they are unable to produce the chemicals and enzymes needed to break down the fibrous plant cells. Therefore they have formed a partnership with the microscopic inhabitants of their gut. This allows the horse, as the host, to absorb the components that were previously inaccessible; locked in the cells.

They even benefit from the by-products created when the bugs digest the plant material. If the horse failed to provide a constant environment for the microbes to live in, these specialized microorganisms wouldn’t survive. Without the microbes, the horse wouldn’t survive.

The evolutionary value of this symbiotic relationship is seen in adaptations that have occurred in the digestive anatomy of horses. One of the major sites for microbes to ferment the food is in the caecum. This is part of the large intestine and has a volume of approximately 60 litres in a large horse. By contrast, in humans, the caecum is a small stretch of the large intestine measuring 3-8cm long.

The remainder of the large intestine in the horse is also voluminous to maximise fermentation and nutrient absorption. Equids, like humans, are host to bacteria, archaea (single-celled organisms) and viruses, as well as protozoa and fungi. All of these play active roles in the fermentation of the food, but their exact contribution is still largely unknown. The proportions of these organisms differ between people and horses, but also between individual animals.

Core members vulnerable to change

Recent research has suggested that a “core” functional group of human gut bacteria can be found in healthy people despite geography or diet. But this group is disrupted when a person suffers from a metabolic disease. This raised the question as to whether this was also true in horses.

A couple of equine studies found that although a core bacterial group could be found, the size and diversity was less than that reported for other species. The impact or reason for this is unknown. It may explain, however, why the equine large intestine is so vulnerable to dietary change, which rapidly effects the health of the host, such as through colic or laminitis.

Diet changes the bacterial population

For many high-performance horses, the daily forage ration is complemented by starch-rich grains or energy dense plant-derived oils. Previous research has shown that starch-rich foods have a large impact on the composition of bacteria in the gut compared to a fibre based diet.

A study funded by Waltham set about to compare a high fibre diet with two similar diets that were supplemented with grains or oil. The results showed that gut bacterial populations weren’t the same between the three diets.

Overall the changes were greater with the starch-rich ration. This is because a bacterial population will change in response to the host eating different foods. This is true for horses and humans alike and is due to bacteria being specialised depending on their and the host’s food.

For example, some bacteria are great at breaking down starch, whilst others rule when a diet is dominated by fibre. Whilst the presence of one type of microbial population rather than another may not affect the horse’s wellbeing, it is the potentially rapid change that can impact health.

Colic, or gut pain, is one such example. Making gradual changes in the diet between high fibre forages as well as complementary feed can help to reduce the risk of such sudden changes in the microflora. Find out if you are feeding you horses enough hay here.

Understanding the role of bacteria

Bacteria are the most numerous type of microbe in the equine gut. Scientists are beginning to understand their role and how diet can influence this population. But one of the first obstacles to overcome was sampling this specialised ecosystem. It wasn’t clear whether bacteria sampled from the faeces reflected those living within different parts of the digestive tract.

Initial work from a collaboration between Aberystwyth University and Waltham compared digesta samples from the digestive tract of horses that had been euthanised for non-research purposes. They found that, as in humans, the last part of the small intestine (ileum) had a lower diversity of bacterial species compared to the large intestine. The microbial populations sampled from the caecum, a digestive cul-de-sac, were different to those from various locations in the colon, which has a unidirectional flow. The microbes found in the faeces were also not the same as the caecum. However, similarities were found between the bacterial population in the right ventral colon (another major site of fermentation) and the faeces.

This horse isn’t the same as that horse

We can all see that one pony doesn’t look the same as the next. But this is also true of the microbes that live in their guts. In fact, even in the same pony on the same diet, these populations can change over time. Over a period of 12 to 72 hours, the bacteria found in an individual's faeces were very similar.

However, after 6 to 12 weeks, the type of bacteria and their numbers had shifted, despite the horses being fed the same diet. Over much larger time scales, changes have been seen. As with humans, ageing in horses has also been shown to be associated with a reduction in the diversity of the bacteria present.

Press release by Waltham Petcare Science Institute