The horse is one of the most impressive natural athletes in the world. It's innate ability is largely due to a specialized circulatory system that, along with the respiratory system, can accommodate the large oxygen demands of the muscles in an exercising horse.

The equine circulatory system consists of two major organs, the heart and spleen, which are connected by a vast array of vessels that serve to deliver oxygen and nutrients to the cells of the body and remove wastes and toxins those cells produce.

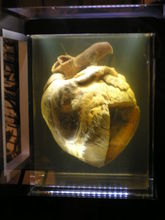

Racehorse Phar Lap's heart

It was found that this exceptional racehorse had a remarkably large heart, now on display in the National Museum of New Zealand.

© 2006 by A.Y. Arktos

The size of the average horse’s heart is approximately 1% of its body weight, meaning a 1000-pound horse will have an eight to ten pound heart! Thoroughbreds are known to have slightly larger hearts in relation to their body size, while draft breeds have hearts that weigh only 0.6% of their body weight.

Not surprisingly, heart size is associated with athletic ability and the famous Australian racehorse Phar Lap was reported to have a heart (now on display at the National Museum of Australia) that weighed 13.6 pounds!

However, despite years of research, measurements of the heart, or Heart Score, cannot predict the athletic potential of a horse. The blood volume of a horse is roughly 8% of their body weight in kilograms, so the average adult horse (500 kg) has approximately 40 liters of blood circulating through his body.

The Complete Circulatory System in the Horse

The horse’s heart is much like our own. It has four chambers, two atria that sit above two ventricles separated by four valves. Blood returning from the body enters the right side of the heart and the deoxygenated red blood cells (RBCs) fill the right atrium.

By passing through the tricuspid valve, the blood moves into the right ventricle. With the contraction of the right ventricle, blood is pumped through the pulmonary valve into the pulmonary artery and through the lungs.

While passing through tiny capillaries that surround the microscopic blind-ended sacks in the lungs (called the alveoli), the RBCs drop off carbon dioxide to be exhaled and attach oxygen molecules to the hemoglobin complexes within the cell.

Once the blood is fully oxygenated it returns to the heart, entering the left atrium. The mitral valve is the gateway between the left atrium and left ventricle, with its thick, powerful muscular walls. The strong contraction of the left ventricle pumps blood through the aortic valve into the aorta and throughout the entire body.

Arteries are the vessels that travel away from the heart, carrying oxygen and nutrient-rich blood. As this blood reaches the capillaries within the tissues, oxygen is released and carbon dioxide and other cellular waste are added to the bloodstream.

Veins travel from the tissues back to the heart. Blood that circulates past the intestines, collecting digested nutrients, is collected in the portal vein and passed through the liver for processing and detoxification. Waste is also filtered out of the blood as it passes through the kidneys.

The Cardiac Cycle

Adult horses have a resting heart rate between 28 and 44 beats per minute. This rate increases steadily as the level of exercise increases and averages 80 bpm at the walk, 130 bpm at the trot, 180 bpm at the canter, and up to 240 bpm while galloping.

Cardiac cycle at work

Racing stresses the cardiac system as liters of blood circulate through the system powered by a heart rate above 200 beats per minute.

Heart rate can also be increased by anxiety, pain, dehydration, anemia, and fever. The heart beats that you hear when taking a heart rate (lub-dub) is the sound of the valves closing.

As the tricuspid and mitral valves close, after contraction of the ventricles, you hear the 1st heart sound, S1, (lub) and when the pulmonic and aortic valves close after the atria contract you hear the 2nd heart sound, S2, (dub).

On some occasions, two other distinct sounds can be heard during the cardiac cycle. S3 represents the sound of blood filling the ventricles and S4 is heard during atrial contraction. Put together, the cycle that repeats itself is S4—S1 (lub)—S2 (dub)—S3.

The Spleen

The second organ that is involved with the circulatory system is the spleen. Lying on the left side of the horse against the body wall, the spleen plays an important role in the horse’s immune system by removing damaged or diseased white blood cells and RBCs from the circulation. It is its participation in the cardiovascular system that helps horses become the tremendous athletes that they are.

When a horse is relaxed, the spleen is also relaxed and expanded to its largest size, extending from the 9th rib space all the way back to the point of the hip and covering the majority of the left side of the abdomen. In this state, it can hold an estimated 30 liters of blood that slowly moves through the spleen then re-enters the circulation.

Under the influences of stress and excitement (in a race, before the jump-off, or when the “fight or flight” response kicks in) the spleen can contract, expelling up to 25 liters of the stored blood into the vessels, making the extra RBCs available to transport a tremendous amount of oxygen to the muscles.

This can nearly double the oxygen-carrying capacity of the bloodstream and improve the aerobic capabilities and athletic efficiency of the horse within seconds.

Components of Blood

Within the vessels the blood is comprised of many factors. It has already been mentioned how the RBCs function to carry oxygen to and carbon dioxide away from the tissues. White blood cells are the infantry cells of the immune system’s army, attacking and killing bacteria, viruses, and other pathogenic invaders.

Platelets are specialized cells that aid in clot formation where there is damage to a blood vessel, such as a laceration. These cells are produced in the bone marrow before being released into circulation. All of these cells are suspended in plasma, a pale yellow solution of water, proteins, electrolytes, clotting factors, and hormones.

Over 30 different blood factors have been identified in the horse, with seven of these groups being widely recognized. Only two blood types, Aa and Qa, are considered relevant when checking compatibility for blood transfusions.

Blood typing can be very useful before giving a transfusion, but because the majority of horses do not have naturally occurring antibodies that could cause a reaction, the first time a horse receives a transfusion it can be done without cross matching and without risk of reaction.

Assessing the Cardiovascular System

Evaluating the cardiovascular system can give us insights into not only how the heart is functioning. It can also give information on the hydration status of the horse. To fully evaluate the cardiovascular system you must do more than just listen to the heart.

Each heart sound should be crisp with no prolonged sounds before or after the actual beat. Abnormal heart sounds are called murmurs, and because the heart sounds are associated with the closure of the valves, murmurs indicate valvular issues.

Listening to a horse's heart

Despite its large size and great capacity, listening to a horse's heart beat requires practiced concentration.

The heart rate is typically heard on the left side of the horse, but because of the size of the horse’s heart, only three of the four valves can be appropriately evaluated on this side: the mitral, the aortic, and the pulmonic valves. In order to assess the tricuspid valve, you must place your stethoscope on the right side of the thorax.

The mitral and aortic valves are most commonly affected with degenerative changes that can lead to murmurs. Murmurs can also be heard with congenital heart defects that lead to blood flow across holes or defects in the heart. To diagnose the cause of a murmur an echocardiogram (ultrasound of the heart) must be performed.

The rhythm of the heart should be regularly regular, meaning there is consistent spacing between each heartbeat and that the interval does not change over time. If there is an alteration in the rhythm of the heart, it is known as an arrhythmia.

Arrhythmias indicate a disruption in the electrical conduction that dictates the contraction and rhythm of the heart and can only be properly classified by analyzing an electrocardiogram (ECG) of the heart. The most common arrhythmia in the horse is atrial fibrillation, identified by an irregularly irregular rhythm.

A-fib can be seen in horses with electrolyte imbalances, but is more commonly caused by enlargement of the atria, often secondary to valvular disease. Treatment protocols involving antiarrhythmic drugs or electrical stimulation can return the heart to a normal rhythm.

Another location where the heart rate can be assessed is at the facial artery that runs along the mandible. Here you can not only palpate the pulse under your fingers, but you can assess the pulse quality. A strong pulse is indicative of normal vascular volume, while a weak pulse indicates hypotension (low blood pressure).

A horse's blood pressure is on average 120/70, similar to humans. Unlike humans, horses rarely become hypertensive (only in cases of severe kidney disease), and they do not develop arthrosclerosis (hardening of the arteries) or plaques in the vessels. Because of this, horses do not suffer “heart attacks” (myocardial infarction) in the same way humans do.

Sudden death in horses is often caused by rupture at the root of the aorta. While hypertension is rare, hypotension is commonly seen in cases of dehydration, colic, blood loss, and other illnesses associated with sepsis.

Due to the hair coat and often pigmented skin, we have to use the horse's mucous membranes (gums) to aid in our evaluation of the circulatory system. The mucous membranes should be pink and moist. Pale membranes reflect anemia, and hyperemic (bright pink to red) membranes occur with sepsis and severe inflammation.

The capillary refill time (CRT) is used as an estimation of hydration. By firmly placing your finger on the gum, you push the blood out of the capillaries and leave a blanched print. The time it takes for the pink color to return to that area is the CRT. Normal CRT is between 1.5 and 2.5 seconds. Prolonged CRT is an indication of dehydration.

The blood is comprised of 30-40% red blood cells, a value we refer to as the Packed Cell Volume (PCV). The PCV of a horse can decrease if they lose whole blood or RBCs (anemia). The decreased amount of water in the bloodstream means the blood is more concentrated, increasing the relative percentage of RBCs, and therefore the PCV (also known as hemoconcentration).

Veterinarians routinely use the PCV to estimate the hydration status of horses and to monitor response to therapy.

So the next time you are performing a dressage test, completing a cross-country course, or just going for a trail ride, think of the complex cycle of the heart, the miles of veins and arteries and the millions of RBCs traveling through your horse’s system, providing the energy and oxygen needed for every step of the way.